On this page you will find a brief history of Brimington. Included are the following subjects:

- Early history, population, the manor

- Communications (roads, canal, railways, buses)

- Economic history (industry, agriculture shops and public houses)

- Education

- Religious history

- local government (including social housing, gas, electricity, water and sewage)

- Social history (Brimington Club, social clubs and societies, famous people

- There’s also information on Brimington Hall and Tapton Grove.

Please note that this is not a complete history of the parish. We will periodically be adding further information.

Our thanks are due the Derbyshire Victoria County History (VCH) for sharing their draft parish history for Brimington with us, from which some of this text is taken. VCH prides itself on new research, including source references – but we have not used these in this account.

Other printed sources have included contemporary trade directories, Vernon Brelsford’s 1937 ‘History of Brimington…’; WTG Burr’s paper on ‘Brimington’ which appeared in the East Derbyshire Field-club yearbook of 1923 and ‘Brimington: the changing face of a Derbyshire village’ edited by Philip Cousins and published in 1995.

If you would like details of any information sources on this page please contact us. You will find that information on this page has generally been newly researched and does not rely on other sources such as Wikipedia.

Introduction

Brimington is a civil parish which lies within the Borough of Chesterfield in the county of Derby. Its population is currently of some 8,000 residents. In 1904 the parish was said to contain 1,329 acres. Following a small boundary adjustment with Chesterfield in the 1920s, in 1936 it was said to comprise 1,283 acres.

Brimington is situated about two miles north east of Chesterfield. It is bounded by the river Rother, Tapton, Calow and Westwood (Inkersall). The parish includes the area known as Brimington Common to the south and New Brimington to the north. The common was enclosed by an Act of Parliament of 1841 (enrolled in 1853). Until that date it was said to be a very wild place, with few houses. New Brimington was developed during the late 19th century, primarily to provide housing for the adjacent and growing Staveley ironworks, which have now closed.

The parish changed during the industrial revolution from being one of an agricultural nature to primarily a dormitory role – providing housing for nearby industry.

19th century terraced housing was built to provide accommodation for those working in local collieries, iron works and factories. For the parish, whilst having some small-scale industry, had no major centres of employment within it.

Further building has occurred since the 19th century. Social and private housing has been constructed, including estates. There is some ribbon development, particularly along Manor Road – towards Calow.

Today it is just about possible to imagine Brimington in its original form. A small village with farmsteads in the centre, surrounded by fields.

Population

It is not intended to give a full account of population changes in the parish. But below are some figures, which indicate the rapid growth of population, particularly in the 19th century.

- 1670 – based on the hearth tax assessments there were some 150 people in the parish.

- 1787 – James Pilkington estimated that there were 400 people.

- In 1801 the population was 503.

- By 1851 this had risen to 1103.

- Twenty years later in 1871 the population was 2403.

- Another twenty years saw the population nearly doubling again to 4034 in 1891.

- By the turn of the 19th century, in 1901, there were 4569 residents.

- One year later, in 1911, the population was 5299.

Thereafter the growth slowed until there was another leap from 5,999 in 1951 to 8,163 in 1961. This was no doubt down to post war construction of homes.

Pre-history and onwards

Little in the way of pre-historic remains have been found or reported in the parish.

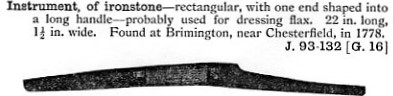

In 1778 workers improving Station Road discovered an ironstone instrument. They had found it in a nearby field that they were excavating for stone. The instrument was supposed, by Dr Pegge, to be a possible ‘fighting club of the Britons’, but it has also been described as used for dressing flax. It was 22-inches long, including a 2-inch handle, with a slight arc. The item made its way to Weston Park museum at Sheffield but has not survived.

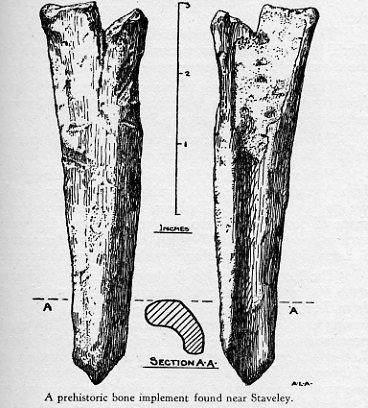

A prehistoric bone implement that Dr Arthur Court described in his ‘Staveley my native town’ book as ‘found on the road to Chesterfield…’, was more probably found in the Tinkersick area of Chesterfield Road, near the boundary with Tapton. This artefact was in Court’s possession but is now lost. It has also been described as a boring tool.

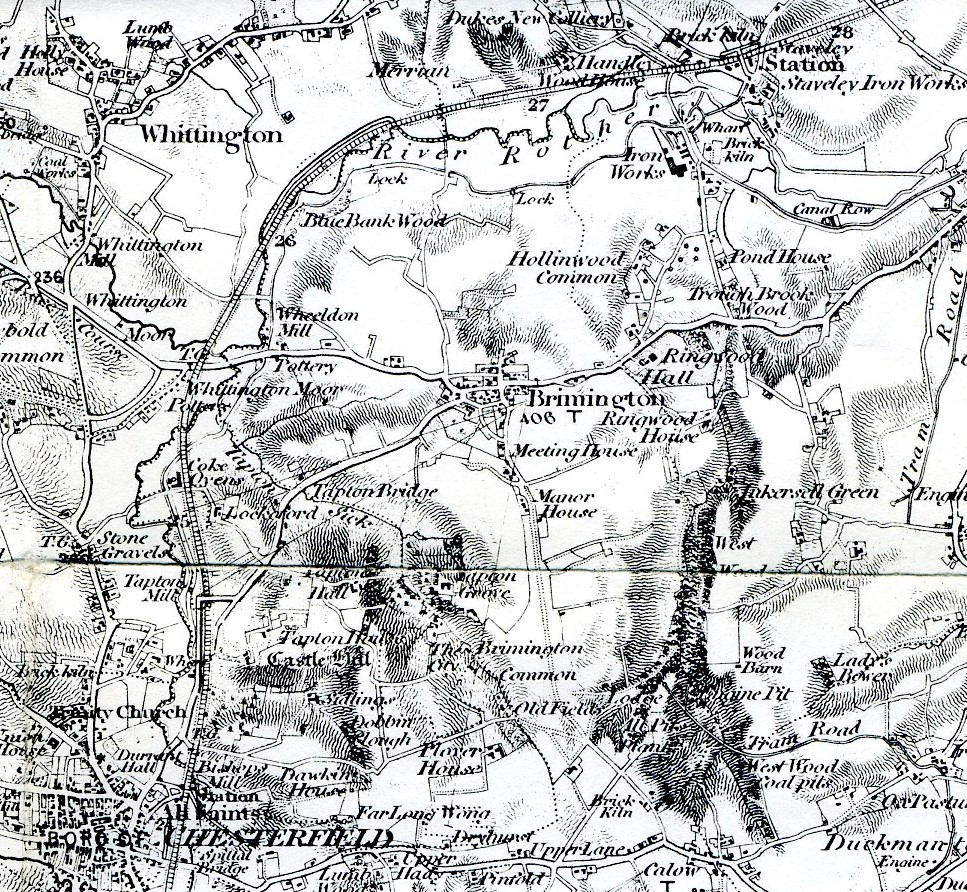

There has been some debate, over a number of years, regarding the route of the so-called Ryknield Street from the Roman fort at Chesterfield to Templeborough at Rotherham. It is currently thought that the route would most likely have followed the Rother valley, which would place the road in the Wheeldon Mill area of the parish.

A field in the Chesterfield Road/Cotterhill Lane/North Moor View area, possibly partly within the medieval core of the village, has fairly recently been found to contain evidence of Romano-British occupation. Iron slag was also found – probably the product of medieval iron smelting. In 2019 archaeological trial trenches, as part of a housing development planning application, identified modest but definite evidence for occupation. A much fuller excavation was undertaken 2022, in advance of building. This has more fully explored the possible occupation of a hilltop site in the Roman period in the village, along with middle age exploitation of ironstone for smelting. Results of this work are still awaited, but are expected to be published in a future Derbyshire Archaeological Journal (information as December 2023).

The Manor of Brimington

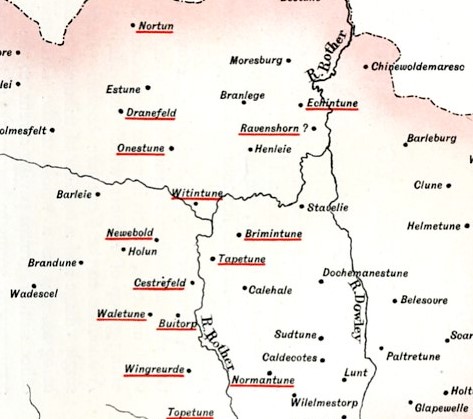

In 1086 Brimington is noted in the Domesday book amongst six berewicks of the royal manor of Newbold (Whittington, Tapton, Chesterfield, Boythorpe and Eckington ).

The Brimington place-name probably derives from a personal name ‘Breme’, with the suffix ‘tun’ (ton) meaning farm. Inclusion in the Domeday book indicates that the area was occupied and farmed before the survey was undertaken.

In 1204 Brimington, alongside the rest of the Manor of Chesterfield (including Newbold), was given to a William Brewer. One of William Brewer’s daughters – Isabel – took the then separate manor of Brimington to Baldwin de Wake, when she married him in 1233. At various times thereafter, usually by marriage arrangements, Brimington was in the hands of the Bretons, the Loudhams and the Foljambe families. The Foljambes were selling land in the 1630s including, it is thought in Brimington. In 1801 the only Foljambe property remaining were two cottages and 5 acres of land adjoining Brimington Common.

A John Dutton held the title of the lordship of the manor of Brimington in 1817. By 1841 the title had passed to George Hodgkinson Barrow, the owner of the Staveley ironworks. By 1852 his younger brother – Richard – was said to be lord of the manor of Brimington. On Richard’s death the title then passed to his nephew – John James Barrow. This Barrow moved from Ringwood Hall in 1875. The title was not mentioned in contemporary directories from 1904 onwards, so was presumably largely obsolete by this time.

In October 1920 a sale was held of land that was the estate of Mrs DM Barrow. It is likely that this included formerly manorial property.

Manorial buildings

The Brimington family presumably lived in the village between the 12th and early 14th centuries. This may have been in a house on the site of the now demolished Brimington Hall (on Hall Road, in the centre of the village – see below). After the manor passed to the senior line of the Breton family the hall would presumably have been let. The house was sold in 1633 as part of the Foljambe family’s property sales. Thereafter it has a separate history to that of the manor.

There is some passing evidence of an potentially earlier Foljambe property to Brimington Hall, elsewhere in the village centre, on the site of the present Cooperative store, though this has not been verified.

Other estates

Brimington had a number of small and medium sized freehold estates in the 18th and 19th centuries. There were, for example, 29 owners assessed for the land tax in 1786. In 1853 there were over 90 owners of land, but only one of these owned more than 200 acres, four between 100 and 200 acres and seven with between 50 and 100 acres.

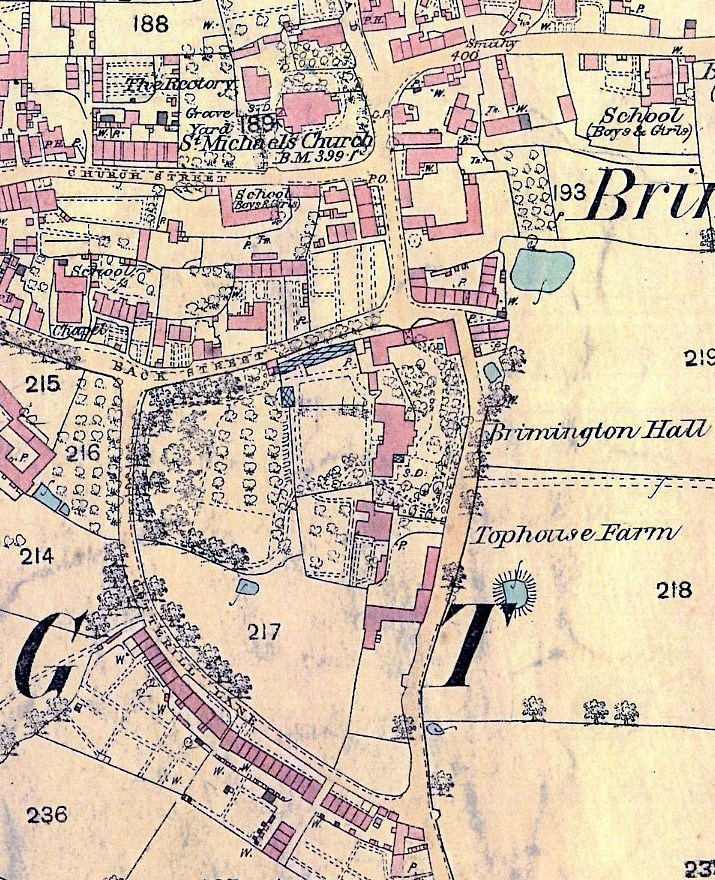

Brimington Hall

What was presumably the site of the manor house, gardens and land was bought from the Foljambe estate by Colonel Gill in 1633. He appears to have built (or possibly rebuilt) the house, which was of stone, with a stone-flagged roof, of two and three storeys, with ashlar quoins, coursed rubble walls, mullioned windows and diagonally set chimney stacks. All these features are consistent with a date of 1639 said to have been carved in woodwork in one of the bedrooms. The interior also contained a fine oak staircase, moulded plaster ceilings, and an impressive over-mantel containing figures and other decoration. A Mr Gill was assessed on 11 hearths in Brimington in 1670, presumably for the hall.

In 1677 an Edward Gill of Carrhouse died, leaving all his goods at Brimington Hall to one of his sons John Gill. Edward’s younger son Henry had purchased the Oaks at Norton in 1681, but there is a reference to Brimington Hall still being with the Gill family in 1720.

In 1715 Henry Gill’s oldest daughter became the Gill Heiress. She had married Richard Bagshaw of that ancient Derbyshire family in 1699. This brought land at Brimington intoi the Bagshaw family’s hands. Perhaps having two properties – Brimington Hall and The Oaks – not that far away could have precipitated the Hall’s sale to the Heywood family after Henry Gill’s death in 1715.

An early 18th century plan shows the Hall as part of George Heywood’s estate. A 1755 plan goes not show the hall as part of Richard Bagshaw’s estate, so it must have been in the Heywood family’s hands between 1720 and 1755.

In 1770 Hannah Heywood, heiress of George Heywood, married the Rev Daniel Ewes Coke of Suckley. This brought the hall to the Coke family when George died in 1784.

In 1817 it was said that the house was divided into tenements and occupied by labourers. It was later restored and occupied by Colonel ET Coke (D’Ewes’ son), who lived there between 1835 and 1848. He made many changes to the both the entrance arrangements and the hall itself. It then appears to have been let to a succession of tenants. (Barbara Rich has written about a fatal accident (in 1846) involving one of the tenants of the Hall in our Miscellany 13).

In 1864 it became the home of Charles Markham, the managing director of the Staveley Coal & Iron Company, until 1873, when he moved to Tapton House (Violet, Charles Paxton, Arthur Basil and Ernest Markham were all born at Brimington Hall). It appears to have been brought by Richard Barrow, who then leased the Staveley concern, specifically for Markham to live there. At the same date (1864) a sale is also held of Col Coke’s furniture at the Hall.

After a period of being let out again, in 1879 mining engineer Richard George Coke purchased the hall and lived there with his family. Richard was Col ET Coke’s brother. After Richard’s death in 1889 it was sold to the Staveley Coal & Iron Company, who used it as a residence for their general managers, first George Bond (d. 1896) and afterwards Henry Westlake.

In 1917, possibly as a result of the death of Westlake’s wife, the then contents of the hall were sold (Westlake moved to Murray House, Tapton). After this the Hall appears not to have been occupied.

Chairman and managing director of the Staveley Coal and Iron Company, CP Markham (Charles Markham’s son), who had been born at the hall whilst it was occupied by his family, offered the building to the village for a club and recreational facility. Unfortunately nothing concrete came of this proposal, although local organisations, such as the Brimington lawn tennis club and the Staveley company’s Brimington ambulance division, used the building.

With no use for the building, the hall was demolished in stages in 1924, 1931 and 1936, although the Staveley Company did not sell the site until 1945.

Some of the interiors were sold to a London dealer for salvage and may have been exported to America. A chimney piece was vandalised before it could be saved for the parish by the council’s clerk Vernon Brelsford. The entrance gate was saved and stored for many years at the rear of Hinch’s butchers on Church Street. It was latterly in an advanced state of decay and destroyed in the 1970s when those premises were demolished.

It was intended that some of the stone would be saved for use in a new boundary wall in the parish council’s cemetery, on Chesterfield Road, but is is not known if this occurred.

During the Second World War an emergency water tank was constructed on a small portion of the site, adjoining Manor Road. For a short period in the 1930s and 1940s a small outbuilding on the site appears to have been used by the Brimington Electric Supply Company, who also had a brick built electricity sub-station towards the very rear of the site.

The site was compulsorily purchased by Chesterfield Rural District Council in 1960 and later landscaped by the borough council, shortly after 1974, creating a public open space fronting Hall Road. Before this parts of the hall foundations and some walls were still visable, the site being largely overgrown. A gas lamp standard also survived near to the former entrance off Hall Road.

In 1970 a local school teacher, Harry Lane, who was an amateur archaeologist, undertook an archaeological excavation on the site with pupils from Brimington boys’ school. Unfortunately, no records of the excavation have survived. Everett Close was constructed on the site of the former hall’s paddock in the 1980s.

What memories there are now of Brimington Hall have receded into the past. Today most of the land is a grassed area, planted with trees. There are some remnants of the stone boundary wall on Cotterhill Lane, near Everett Close, and on Manor Road.

Tapton Grove

Despite its name Tapton Grove is actually in Brimington Parish.

At the end of the 18th century either Joshua Jebb, a Chesterfield hosier who died in 1798, or his younger son Avery built a house to the west of Brimington Common, close to the boundary with Tapton, which became known as Tapton Grove. The grounds, which included a lake formed by damming Tinker Sick, extended into Tapton township. Joshua Jebb’s elder son Samuel built Walton Lodge, which stood in rather more extensive parkland in Walton township to the west of Chesterfield.

Avery Jebb married Amelia, the daughter of Richard Bower of Goss Hall in Ashover, with whom he had a son Richard, the owner of Tapton Grove in 1817, who died without issue, and a daughter Mary Anne, who married Godfrey Meynell (1779-1854) of Meynell Langley, near Derby, to whom Tapton Grove passed after Avery Jebb died.

In 1829 the house was the home of Charles Wake and in 1833 it was let to the Chesterfield attorney, Bernard Maynard Lucas. In 1846 it was occupied Godfrey Meynell’s son John, who was killed in a railway accident near Clay Cross tunnel in 1851. In 1870 Richard George Coke (later to live in Brimington Hall) was living at Tapton Grove, although the Meynell family remained owners of the estate until at least 1888. By that date the tenant was Mansfeldt Forster Mills, whose son Robert Fenwick Mills had purchased the freehold by 1895. He was still at Tapton Grove in 1912, but died in 1928. The Mills family were especially associated with the Chesterfield Brewery Company. Tapton Grove was subsequently purchased by a branch of the Chesterfield Shentall family.

The last family to live at Tapton Grove, were the Shorts, who effectively owned Pearson’s Pottery on Whittington Moor. Fredrick Stanton Short purchased Tapton Grove when it was sold by the Shentall family. His wife was a Shentall – so she had lived with her family at Tapton Grove. The Shorts left Tapton Grove in the 1970s.

The property, which is Grade II* listed is currently a nursing home. The adjacent Grade II former stable block has recently been restored and extended for further client accommodation.

Ringwood Hall

Ringwood Hall is not in Brimington – it is actually in Staveley parish, though the parish boundary runs nearby and many refer to it as being part of our parish. This Regency style house (it was never a manor house), now an hotel, was completed in 1830 for George Hodgkinson Barrow, who then leased Staveley works. The architect is unknown. If you want to find out more about Ringwood Hall, read our brief chronology blog post by clicking on the link here.

Other buildings and historic sites

There are and were other buildings and sites in the parish of historic or architectural note. Brimington was subject to, like many such villages, widespread clearance and demolition in its centre during the 1950s, ’60s and early ’70s. Some of this, particularly in the immediate post Second World War years, was due to unsound properties, with poor facilities. Today we might well rehabilitate these cottages and houses, but in the 1950s efforts were concentrated on constructing sound houses, with electricity, running hot and cold water, bathrooms and water closets. Some losses were questionable. Did the National School building in Church Street and the nearby former Hinch’s butchers shop (which could well have been 17th century) really had to be demolished?

Never-the-less, there are some notable buildings still to be found in the parish. Many of these have been listed as being of architectural and historic merit and can be found by searching Historic England’s website.

Derbyshire County Council has also a number of entries on its Historic Environment Record for Brimington. Some of the entries, however, must be treated with a little caution.

Field patterns, presumably mediaeval (or later), were still discernible in the area developed for housing in the early 1990s around the present Nether Croft Road area.

Communication

We deal with the Roman road Ryknield Street in the section ‘Pre-history and onwards’ above and also in our ‘Brief History of Tapton’ page.

The main A619 trunk road, which runs through the centre of the village on its way from Chesterfield to Worksop, is a a former toll road upgraded under the Chesterfield and Worksop Turnpike Trust, 1738 until the trust was wound up in 1882. There was a toll house, with gates, on Ringwood Road.

The A619 is joined by another former toll road – now the B6050 (Station Road) – at the junction of Devonshire Street, Chesterfield Road and Church Street. This leads down towards the parish boundary at the river Rother. It was turnpiked by the the Brimington, Chesterfield and High Moors Turnpike Trust in 1766. This trust was wound up in 1886.

An ‘Old River Bridge’ was mentioned in Quarter Sessions records in March 1831. That year it was ordered to be repaired. Burdett’s 1767 map of Derbyshire shows two roads from Brimington crossing the Rother, with a third to Brimington Mill (at Wheeldon Mill) which then ended at the river Rother. The latter is the modern Station Road. It is thought that the turnpike trust originally built this ‘Old River Bridge’, when it made a new section of ropad towards Whittington Moor. This area of Station Road was altered when the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway (later Great Central) constructed its line from Staveley to Chesterfield and then Heath in the early 1890s. It’s most likely that the ‘Old River Bridge’ was reconstructed by the railway company at this time. The turnpike trust had been wound up in 1886 and the bridge would have become the responsibility of the county council from 1889. Despite this it’s still marked on later editions of Ordnance Survey maps. (There’s more about local county bridges in our blog).

A non-vehicular road continues from the end of the present Coronation Road, running northwards to New Whittington. This road – Cow Lane and Bilby Lane – is the most direct route to New Whittington, but is not in vehicular use.

Antiquarian Dr Pegge stated in his 1780 account of the plague in England that the most direct route to Whittington and thence to the peak district was via Gregory Lane. This branches off the road referred to above but now abruptly ends pointing towards Whittington. Dr Pegge tells us that this route formerly made its way across the Rother by a bridge, but that this was pulled down around 1603-4 to stop the spread of the plague. He also stated that this route ‘…was then a great road for packhorses from the vicinal parts of Derbyshire and Yorkshire, which, after they had crossed the water, proceeded through Brimington, and over the moor there, for London.’ Eventually a new route was created, with a new bridge, hence the name of the road which runs from the present B6050 Station Road, to Whittington – Newbridge Lane.

The lone pedestrian is walking over the bridge to the Chesterfield Canal. Just beyond, to the left of him, was the former Sheepbridge and Brimington railway station, the line running under the road. There has been much industrial activity in the Wheeldon Mill area. To the left, where the now demolished house stands (the first of a row of terraced properties) was a short-lived early 19th century pottery. Hereabouts were also coal and ironstone mines, a brickworks and wind mill (further back up the hill to the right), not to mention a greyhound racing track. The Mill public house (the Great Central Hotel at this time) is to the right, out of picture. The parish border follows the route of the river Rother in this area – a little way beyond the telegraph pole. To the right of that pole, a little way back, was a water powered corn-mill.

(Pegge also recorded a local tradition that cabins had been erected in a field called ‘Cabin Close’, later crossed by the Chesterfield Canal, at the bottom end of Bilby Lane. These were presumably to isolate those suspected of having the plague. There is no evidence that anyone was actually buried in this area. We have published blogs on this issue which you can find starting here).

The unclassified Manor Road leads from the village centre southwards to the parish of Calow. The majority of this road was laid out as a result of the Enclosure award (see below), which results in its relative straightness.

The Chesterfield Canal runs through the north and east of the parish. This was opened from Chesterfield to West Stockwith in 1777. There were formerly a number of wharves onto the canal, in the parish. Particularly noteworthy was Dixon’s Wharf, which, in the 19th century, was used for transhipment of materials and goods to a glassworks at Whittington, via a tramroad. The canal became largely disused after Norwood tunnel collapsed in 1907, isolating the Chesterfield section. After many years of disuse the canal was restored progressively in the parish, from the 1980s onwards, and is now a popular leisure attraction.

The former North Midland Railway (later Midland Railway) route runs through a portion of the parish, to its north and north-west boundary. This route, from Derby to Rotherham Masborough, opened in 1840. Its construction brought George Stephenson to Tapton House. There were and are no stations in Brimington on this railway, which is still in use.

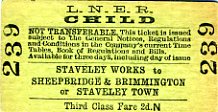

The same cannot be said for the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway Company (later Great Central Railway), which constructed a line in the late 1880s and early 1890s from what later became its mainline to London, at Staveley (Lowgates). This eventually formed a loop through Chesterfield, re-joining the company’s line in the Heath area. There was a railway station on this line near the parish boundary with Whittington, at Wheeldon Mill, which opened in 1892. The line paralleled that of its Midland Railway rival in the northern extremes of the parish. The station, latterly known as Sheepbridge and Brimington, was closed in the mid-1950s. Nothing now remains of it, except the station master’s house, which is still in residential use. The loop line itself closed to passenger traffic in March 1963. In Chesterfield a good deal of the track-bed and the site of the Infirmary Road (‘Central’) station was used to construct the the A619 inner relief road. In the parish a walk ‘The Blue Bank Loop’ uses part of the route. We have published an account of this railway line in our Brimington and Tapton Miscellany 3.

Brimington is still well served by local bus services. Past private bus and coach operators have included Doughty (garage off Church Street), ‘Clocky’ Brown (garage on Chesterfield Road) and Wetton (garage on Ringwood Road), who were all active in the 20th century, but ceased operations some years ago. Chesterfield Corporation commenced a motor bus operation serving Brimington in 1914. Underwoods, later East Midland Motor Services Ltd., have also operated routes through the parish, notably through New Brimington. Today the majority of services are provided by Stagecoach plc, through their Yorkshire operation. A route along Manor Road is run by First South Yorkshire.

We discussed the commencement of the Chesterfield Corporation service in our ….Miscellany 9 and have published local funeral director, bus and coach operator Alan Wetton’s reminiscences in …Miscellany 8. There’s more about GE ‘Clocky’ Brown’s’ business in our blog about him. To find out more about Wetton’s and Doughty’s operations visit our download page, scroll to near the bottom and look for Local operators – Doughty and Wetton – Transpire News Sheet articles 2021.

Other more recent operators of private hire coaches were Ringwood Coaches (garage Ringwood Road – started in 1960) and George Chumbley (garage latterly on the corner of Coronation Road and George Street – now replaced by housing). Chumbley sold out to J Copper & Sons of Killamarsh at the end of 1983.

Economic history

For the majority of its history Brimington was a mainly agricultural parish, until, like many similar communities, it rapidly grew in the 19th century due to the impact of the industrial revolution. Brimington has, however, never had large-scale industry based within its boundaries. Its main employment base was the large industrial complex of the nearby Staveley Coal & Iron Company, coal mining and from industry in nearby Chesterfield.

According to contemporary trade directories, in 1829 there were nine principle farms in the parish, rising to about 20 by the 1840s and thereafter fluctuating between 15 and 20 until 1900. The number fell to around a dozen just before the First World War. It stayed at this level until the early 1930s. By the 1941 Kelly’s directory there were only six named farms in Brimington – Grove Farm, Ivy House Farm, Lodge Farm, Manor Farm and one other. There were three smallholdings including Brookside Farm and Yew Tree Cottage. The chief crops were said to be wheat and oats.

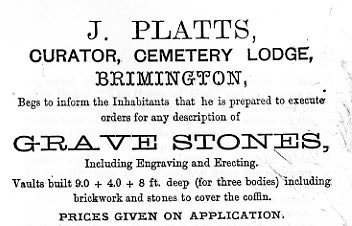

Other manufacturing included those listed below (please note that this is not a comprehensive survey, not all dates, locations and types of industry are covered).

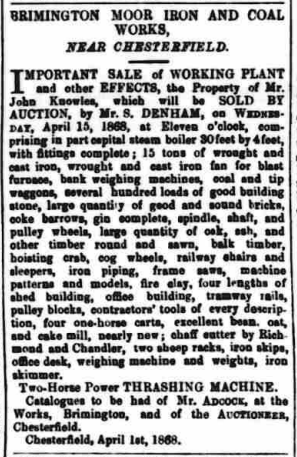

A single blast furnace on Brimington Common – the site of the present Furnace Farm – was operating sometime between 1850 (possibly earlier) and 1858, under a Matlock born railway contractor John Knowles (d. 1869), firstly in partnership with Chesterfield solicitor and town clerk John Cutts (the partnership between the two was dissolved in April 1856). Knowles also had a successful sanitary pottery and refractory business in Woodville, south Derbyshire. Industrial activity on the site appears to have continued for sometime after the single furnace was blown out. (The furnace was hot-blast not cold as previously supposed). The premises were also an operational farm. Henry Bradley‘s father worked as a book-keeper at these ironworks. Knowles also operated coal and ironstone mines. He latterly lived at Knowleston Place in Matlock after a period at Herne House, Calow. His work as a railway contractor also resulted in him travelling and living around the country.

A cornmill was situated on the river Rother at Wheeldon Mill. This appears to have gone out of use by the 1880s. There was also a windmill nearby. The mills were run by a Mr Wilden, whose name appears to have become corrupted, being used to describe the area in which they were situated – Wheeldon Mill.

References to coal and ironstone mining appear in 18th century leases. Local coal mining operators in the mid-nineteenth century include Joseph Smith, George Mycroft and Stephen Sayers. In 1879 the Lockoford Colliery Co. were also operating in the parish. Tinkersick Colliery was operating under the Mason brothers in the mid 1920s. There was also a mine on Brimington Common, the equipment at which was for sale in May 1883. A drift mine was operating in the Wheeldon Mill area into the late 20th century under Gaunt. There was also coal and ironstone mining near the border with Staveley parish, at New Brimington. Paul Freeman describes a colliery – Victoria – and other workings, in his article ‘In search of the Victoria Hotel, New Brimington’ in Brimington and Tapton Miscellany 9. A glance at old Ordnance Survey maps will reveal many ‘old shafts’ in the area, many not yet documented.

Two iron foundries were active in Brimington in the mid 1850s. Bennet Mycroft’s was the longest lasting and was possibly situated in Church Street. It was probably this business that was eventually in the hands of a Herbert Ashmore and which continued until around 1904. A second foundry – Milner’s – was much shorter lived. Both the foundries produced small castings – iron grates, kitchen boilers and the like. Ashmore appears to have produced the cast iron street nameplates which can still be seen in a few areas of village. These were erected after the streets were officially named by the parish council in 1902.

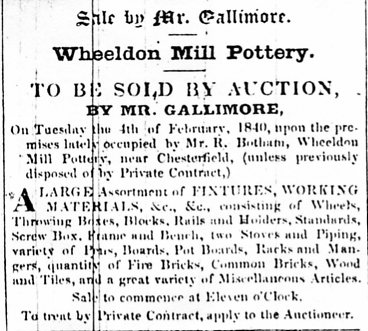

A pottery was briefly established at Wheeldon Mill, on the side of the canal, opposite the present Drake Terrace. It was first mentioned in 1824 when a buyer was sought for the business. After some changes in ownership, the stock and equipment were advertised for sale in 1840. The pottery produced brown ware and stoneware, including bottles. For further information see the article in Brimington and Tapton Miscellany 8; ‘A canalside pottery at Brimington’, by Philip Riden and Philip Cousins. The pot-house building has long-since disappeared.

There have been a number of brickyards in the parish. In 1895 there were, for example, three brickyards mentioned in a trade directory – Nodder at Wheeldon Mill, CJ Saunders at the Calow end of Manor Road and a third owned by Samuel Lancaster of Newbold. In 1928 there was a further short-lived brickworks on Newbridge Lane, run by Fred Holmes. Further information on brickworks in the parish is available in a download of ‘”The Brimington Brick Company” – north east Derbyshire’s brick making in microcosm’ by Philip Cousins and David Wilmot. This was originally published in North East Derbyshire Industrial Archaeology Society Journal, volume 1.

Copperas was manufactured for a short period in the early 19th century at two places in the parish – at the top of Newbridge Lane and at what is now known as Manor Farm, on Manor Road, Brimington Common. For many years the latter was aptly known as Copperas Farm.

As part of a national effort, there were exploratory but unsuccessful investigations for oil, on the Manor Road Recreation Ground between 1919 and 1921. Cliff Lee has written about these investigations in our Brimington and Tapton Miscellany 6, where he comments that, of the several wells sunk elsewhere during the period, the one at Brimington was the first to strike oil. But early hopes were soon dashed and the well was later deemed a failure.

There was also a short lived mineral water manufactory on Coronation Road, along with a jam and preserves factory, which followed it at the same location. For more details see our free download on Brimington’s pop and jam manufactory, available in Brimington and Tapton Miscellany 1. The two businesses together lasted only around twenty years at the beginning of the 20th century. Neither are listed in local trade directories.

Other industries have included a small amount of quarrying, noted in the 1849 Tithe map and schedule. These produced ‘freestone’, generally used for walling and roofing.

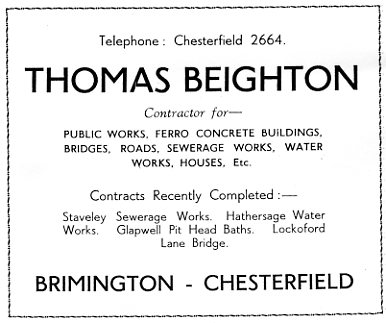

Thos Beighton Ltd had their headquarters on Station Road. A building and civil engineering company they were first established in 1908, becoming a limited company in 1934. By the mid to late 1960s the company were employing some 100-150 persons, but unfortunately went into liquidation in 1971, mainly as a result of problems with a contract at Alsager sewage works. Beightons built many buildings up and down the country. In Chesterfield their last large project was probably the former 1970 Littlewood store, now Primark, in Chesterfield Market Place. They also built bridges and undertook other civil engineering work. The former court house on West Bars, Chesterfield, was another of their construction projects. NLT training services now occupy Beighton’s former offices on Station Road.

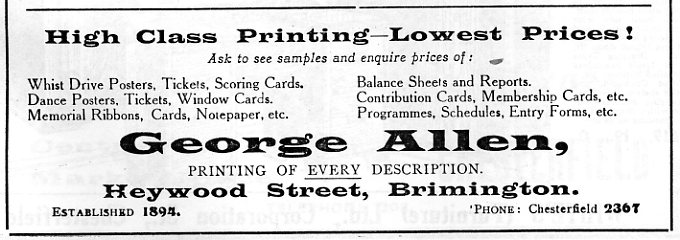

Heywood Street was home to the premises of printer George Allen, established in 1894. The company gained a national reputation as a printer of posters and other theatrical items. The premises are now occupied by housing. Another 19th century village printer was Ringrose. Allen possibly took on his business, but this needs further research.

For a short, but not uneventful time, Wye Electronics had a factory at the former Thos Beighton site on Station Road. They made audio items such as music centres and small components like electrical transformers. The company closed in 1982, after trading on the site for 15 years.

There have been various small industries based at the former station yard, Wheeldon Mill. These have included industrial plant fabrication (e.g. Blair Engineering) and waste disposal/recycling. The site is now occupied by small industrial units and a haulage company.

Perhaps the most unusual industry was that of the Umney family in John Street. In 1937 Vernon Brelsford in his ‘History of Brimington…’ stated that for over 50 years ‘rush mats and baskets‘ had been produced there. Though there was not then much call for the baskets the rush mats were still in demand by the owners of ‘large country residences’. Indeed, we know that Duchess Evelyn Devonshire reintroduced rush matting into the state rooms at Hardwick Hall. The matting was latterly made by two sisters, who lived at number 15 John Street for many years – until comparatively recent times. We do not know when the rush matting business stopped.

Trade directories note that were three public houses in the parish in the 1820s and 1830s. The Bugle Horn (on Hall Road long-since closed and demolished), the Three Horse Shoes and the Red Lion. These were joined in the 1840s by the New Inn, which was later renamed the Great Central – latterly The Mill. It was here that former England and Sheffield Wednesday football player Peter Swan (1936-2021) concluded his career in the public house trade. He had also tenanted the Three Horse Shoes and other local pubs. In the 1880s it is believed that the Ark Tavern, Butchers Arms, Prince of Wales (on the Corner of Cotterhill Lane and Manor Road and closed in 2007, being eventually demolished in 2008) were licensed for the first time. Prior to this they were probably beer houses – which were not fully licensed – they could not sell spirits. The Brickmakers Arms (closed December 2015) and The Miners Arms (closed Christmas period 2022), both on Manor Road, were also former beer houses, the former definitely extant in 1853. The Markham Arms on the former Coal Industries Housing Association estate was opened in 1957 and closed in July 2023, following purchase by a property company. The Mill closed in July 2023. You can read more about the history of the Markham Arms here, of The Mill here and of the Miners Arms here, in our blogs.

(The history of the village’s two social clubs is dealt with below in the social history section).

Like many other similar villages, Brimington became quite self-sufficient for everyday groceries, hardware and even clothes in the late 19th to mid 20th century. There were the usual mixture of shops and businesses.

The Chesterfield and District Cooperative Society opened a branch on High Street in 1909, later on Rayleigh Avenue. There were also sub-branches (i.e. part-time) of the national banks held at various premises including the Congregational Church on Chapel Street.

The main shopping areas were Church Street and High Street. There were small local centres at the bottom of New Brimington and on Manor Road, which both had post offices, in addition to a post office in the village centre.

During construction of the Wikeley Way/Lansdowne Road council estate, a small development of flats with a shop unit below, were constructed in the 1960s on Neale Bank. The Coal Industry Housing Association estate (see local government below) also had flats with a shop below constructed during the late 1950s. Despite campaigns led by the parish council the Neale Bank shopping area never received a sub-post office.

As an example of the variety of local trade in the village immediately after the Second World War, there’s a download available of a 1941 ‘Kelly’s directory of Derbyshire’, which lists Brimington shops and businesses.

Education

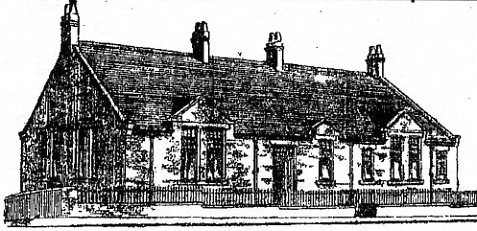

Education was undertaken sporadically until establishment of the Brimington United District School Board in 1876 (‘united’ as it also included Tapton). Like many such school boards it embarked on an ambitious building programme.

Prior to the opening of the board’s schools education was largely carried out by the various religious sects in the parish. A National School (now demolished) was also opened in 1840 on Church Street, opposite the parish church.

Board schools were built on:

- Brimington Common (infants – opened in January 1878, though its headstone has the date of 1877). This school is still in use.

- Devonshire Street (originally an all age school with infant, girls’ and boys’ departments), opened in 1878. It was enlarged in 1888. This school was known as central school for many years and is not now in use.

The board planned for but did not deliver another infant school at Princess Street, but the new education committee of the county council did, in 1904, after school boards had been abolished and replaced. This school is still in use. It is named after Henry Bradley who you can find out more about from our free download.

More recent educational developments can be summarised as follows:

- The opening of Hollingwood Girls’ School in 1941 allowed senior girl pupils from central school to be educated there.

- Brimington County Secondary Boys’ School opened in 1957 on Springvale Road, allowing senior boys from central school to be relocated to this site.

- Hollingwood girls’ and Brimington boys’ merged in 1977 to form a split-site Westwood School, for secondary education.

- Springwell Community School is formed in 1991, after a bitter battle over secondary school reorganisation. This replaces the former Middlecroft School, Staveley (which site it occupied), along with both the Westwood School sites. The former Westwood Upper School (itself the former Brimington boys’ school) was finally closed and demolished in 1992. This results in Brimington being without secondary school premises situated in the village.

- In 1997 work started on a new Brimington Junior School, on the site of the former Brimington boys’ school.

- The old Devonshire Street Brimington Junior School closed at the end of December 1998. In January 1999 the new Brimington Junior school opened at Springvale Road.

The old central school buildings on Devonshire Street, which had become increasingly dilapidated when occupied by the school, were subsequently purchased by JPC Properties and restored as attractive apartments – the scheme being completed in 2001. The original central buildings are listed as Grade II.

Religious life: Church of England

Until Brimington became a separate parish in 1844 it was a chapel of ease to Chesterfield Parish Church.

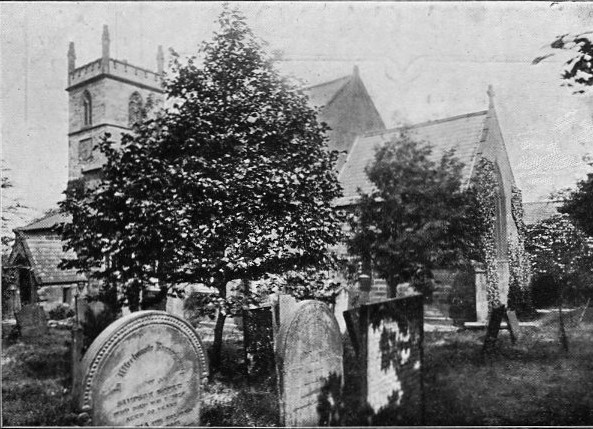

There have probably been three buildings on the site of the present parish church (dedicated to St Michael) in Church Street. The original building was painted by Swiss artist SH Grimm around 1785. The water colour shows a rather decrepit building. This building had a tower added to it by Joshua Jebb in 1796. Proving inadequate the building was replaced in 1808, though the tower was retained. Again proving inadequate, probably due to the increasing population, the 1808 building was replaced with a new church in 1846-7, designed by Sheffield architect Joseph Mitchell. However, the tower was, retained, but heightened and remodelled. A parsonage house was constructed nearby in c.1845.

A church hall was opened in 1913 on Church Street. This is still in use.

The Church of England established a mission church – St Mary’s – on Manor Road, (near the board school) which opened in 1878. This corrugated iron building subsequently closed sometime around 1952/3. It is now the site of housing. We’ve published a series of blogs on this church which you can read here, here and here.

Religious life: non-conformity

Methodists and Congregationalists all appear to have a history of meeting in their own houses in the early years, before they were able to establish their own dedicated buildings. Some research still needs to be carried out to properly identify the location and sequence of the early Methodist meeting houses in the parish, but this is summarised below. It appears that Methodism, particularly the Primitive Methodists, had the largest following in the parish for many years.

The 1835 Primitive Methodist chapel, described in the text, is the building to the right – in this 1960s view – in use as a shop. The property is still extant and is now a house. The stone building to the extreme right was formerly the stables to the Red Lion public house. It was demolished in the 1970s. The shop to the left is Shentall Ltd., general grocers.

An Edwardian view of the 1864 Bethel Primitive Methodist Chapel, which was on Ringwood Road. Robinsons Caravans now occupies the site.

Mount Zion Methodist Free Church was on Hall Road. To the far left is the Ark Tavern public house, believed to have been a former Wesleyan Methodist chapel, and dating from 1808.

Trinity Wesleyan Methodist Church, High Street, pictured around 1901. It is now the Brimington Community Centre

A Wesleyan Methodist meeting house was built in Brimington in 1808. (This is probably the present Ark Tavern public House on Chesterfield Road).

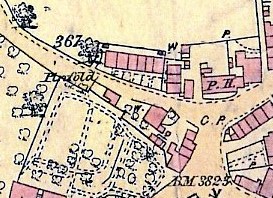

The Wesleyans had another meeting house in Boot’s Yard in the area on Manor Road, to the south of its junction near Cotterhill Lane. Number 42 Manor Road stands near the site. It is marked on the 1860s Ordnance Survey map (near the top of this page). The history of this chapel needs further investigation, but it may have been the scene of a once notorious event when Wesleyan Methodists had to reclaim their meeting house from occupying Free Methodists in 1860.

A Primitive Methodist meeting house was built in Devonshire Street in 1835. This chapel is still extant – next to the Red Lion public house. It is now a private house. The Primitive Methodists moved to a new building on Ringwood Road (Bethel) in 1864.

The Primitive Methodists built chapels in New Brimington (Mount Tabor) in 1881 and Brimington Common (Ebenezer) in 1867. both buildings are still in use.

The Wesleyan Methodists built new premises on Heywood Street in 1881. In 1896 Trinity Church, adjoining the 1881 building, was opened in High Street. (These two buildings are now the Brimington Community Centre).

The Mount Zion Methodist Free Church opened on Hall Road in 1864.

The Bethel church premises on Ringwood Road closed in early 1965. Mount Zion on Hall Road had closed in 1961. The congregations from these went to worship together with the congregation at Trinity.

A new Brimington Methodist Church opened on the former Mount Zion Church site, Hall Road in 1967. Trinity closed as the new building opened.

The Congregationalists opened a building on Chapel Street in 1895. This was originally designed to be school rooms, with a church added later, but this never happened. The church closed in December 2019. Beryl Sharman has written extensively about this church in Brimington and Tapton Miscellany 12.

There have been other sects active in the parish. The Independent Holiness Movement (Heywood Street – now demolished), Spiritualist (hired the Brimington Labour Party Rooms, John Street – now demolished – but still meets in the village) and the Apostolic Church (Chapel Street – now demolished) have all had meeting houses in the parish.

Local government

Little, if anything, is known about how the lord of the manor governed Brimington, as no manorial records survive.

Until the Local Government Act of 1894, which created parish councils, the village was largely administered by the parish vestry. As the name suggests this was a meeting originally held in the vestry of the church. The minister and leading rate-paying parishioners were members. They appointed various officers, such as church wardens and the parish constable. Unfortunately Brimington’s vestry minutes do not survive. They were, however, seen by Vernon Brelsford who made extensive use of them in his 1937 ‘History of Brimington…’ According to Brelsford, the oldest book started in 1675, which means that Brimington was controlling most of its own affairs by this date. One extract that Brelsford noted related to the appointment of a parish ‘pinder’ in 1865. This official was responsible for rounding up stray animals into the ‘village pound’. In Brimington this was situated on Devonshire Street.

Brimington Parish Council first met on 31 December 1894. There were ten parish councillors, who had been elected by poll. The council soon took on responsibly for the cemetery on Chesterfield Road, which had been completed in 1878 by the Brimington Burial Board, but such things as highway matters were already the responsibility of county councils, created in 1888. The creation of parish councils removed direct involvement of the Church of England in local government affairs.

The parish council oversaw naming of the streets in 1902 and lighting of them in 1914. The latter had been the subject of some debate in the parish. The council had first suggested this in 1909 but there was considerable opposition amongst ratepayers.

In reality the council was a fairly muted affair, with most councillors being establishment figures – shopkeepers, business owners etc. who appeared to want to keep the rates down rather than forging a new future for the village.

The 1894 Local Government Act which created parish councils also established rural and urban districts. Brimington became a civil parish in the rural district of Chesterfield. This council – Chesterfield Rural District Council (CRDC) – assumed responsibility for cross parish services, such as housing and sanitation.

In 1974 the CRDC was abolished. A new borough of Chesterfield was formed, which included the parish of Brimington and the former urban district of Staveley.

Rural and urban district councils were given powers to build council housing, but the CRDC had an unhappy record in this regard immediately after the First World War.

Brimington received its first council houses in 1933 and 1935 on Bank Street and Newbridge Lane. There was no further building until after the Second World War – when in 1948 flats were built on Wikeley Way (named after the CRDC’s chief engineer). There followed a rapid building programme. By 1975 there were 779 council homes in the parish, with a major development being the mainly 1950/1960s estate centring on Wikeley Way and Lansdowne Road.

All this was undoubtedly due to political changes in the CRDC when the ‘old guard’ was replaced by a new Labour administration. Our …Miscellany 11 carries an article about the development of council housing in Brimington. Included is a brief review of two of the Brimington councillors involved in the story – Henry Phipps and Walter Everett.

The Coal Industry Housing Association (CIHA) housing estate

The CIHA built a medium sized estate in Brimington for coal mining families in the 1950s. The ‘Counties Estate’ as it was known at the time – every street being called after an English county – was built on a site to the east of High Street, just off the village centre. It is almost exclusively made up of system built houses. At one time houses to the High Street side (top) of the estate, which are made of sectionalised concrete, were all painted white. The area consequently became known as ‘The White City’. The estate is now in mixed hands; either owner occupied or private rented. The white painted houses are now rendered or painted in mixed colours.

Brimington Freehold Land Society

The Brimington Freehold Land Society was formed in February 1876. Its original aim was to purchase 7 acres and 3 perches of land in Brimington, ‘and to divide the estate… into lots, and apportion the same among the members.’ The affairs were run by a committee comprising a president and eight committee-men, chosen by the shareholders. The estate purchased appears to have mainly encompassed todays John Street. Plots were available, which were generally separately developed, resulting in a different style of housing in this street to some elsewhere in Brimington. At one time increasing the number of freeholders had another advantage; they were able to vote in elections. There’s some more information about the freehold land society in our download ‘A history of the site of the former Labour rooms and Brimington Spiritualist Church’.

Utilities

Today we take effective provision of utilities such as water, gas and electricity without a second thought. But the situation was once very different.

Gas reached the parish from 1864, when the Whittington Gas Company were given permission to install their supply pipes in the parish’s highways. This company supplied gas until it was purchased by Chesterfield Corporation in 1921. There were works at the bottom of Whittington Hill, which supplied Brimington (and Whittington). Until the advent of natural gas in the 1970s gas made from coal was supplied.

Water was supplied by another private undertaking – the Chesterfield Gas Light and Waterworks Company. Originally formed in 1825 they extended their supply network into Brimington when they were given powers to do so in 1865. The same act gave them powers to construct the Upper Linacre Reservoir (the Lower reservoir being constructed earlier). Once construction had finished in 1869 it enabled Brimington to be supplied with piped water for the first time. Unfortunately, for Brimington, the company did not have to guarantee a constant supply to consumers who were above their service reservoir at Club Mill, Chesterfield. In practice this was most of Brimington Common. There were many complaints about supply quality (it was not filtered), pressure and taste and there were serious seasonal water shortages. When the company sought parliamentary powers to construct a new reservoir at Holymoorside, in 1894, there was furious opposition throughout the district, led by Chesterfield Corporation. This resulted in the Bill not being proved. March 1896 saw transfer of the company’s undertakings to a new Chesterfield Gas and Water Board. The Board comprised twelve members – two each from the by now urban district councils of Whittington and of Newbold-cum-Dunston; the remainder from Chesterfield Corporation – Brimington not having any membership. We have published a blog about how water came to Brimington. To read this click here.

Electricity generated at the Staveley Coal and Iron Company works, mainly from waste blast furnace gas, was first distributed to selected consumers in the parish, such as those at Brimington Hall, which housed the company’s general managers. In early 1918 the Brimington Electric Supply Company Ltd. was formed. Perhaps not surprisingly most of the directors were Staveley company men as energy was purchased from that source and distributed to consumers in the parish. Similar companies were set up elsewhere. Unfortunately the supply wasn’t standard, but this wasn’t of any great detriment whilst only used for filament lighting. By 1932 there were 942 consumers of the Brimington company. In 1935 the Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire Electric Supply Company (Notts and Derby) were claiming that eight supply companies, like that in Brimington, controlled to some extent by the Staveley company, were illegal. By this time there were 1,184 Brimington consumers. In 1944 the company was wound up and purchased by the Notts and Derby company, for over £15,000. Notts and Derby was nationalised the following year. The East Midlands Electricity Board spent some time and resources in the early 1950s transferring the former Staveley network, including Brimington, to the national grid, with its standard distribution voltage and cycles. By this time difficulty was being caused to consumers who were unable to use electrical equipment unless it was modified.

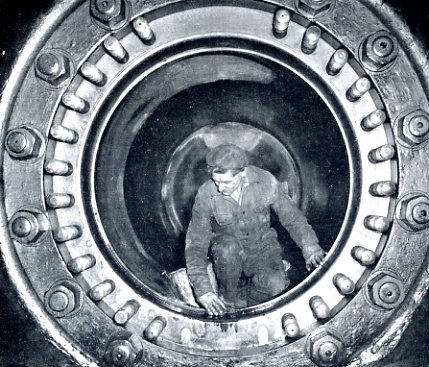

Experimental Sewage treatment was undertaken at Tapton Grove by RF Mills with Dr Barwise, the county medical officer of heath, which led to a Derbyshire-wide adoption of the bacteriological method of sewage treatment. Sewage works, at Wheeldon Mill, running down the hill off the north side of Station Road, to the canal, were established in 1904. These dealt with the majority of sewage from the parish, but other arrangements were made to deal with effluent from New Brimington, Ringwood Road, Brimington Common and housing near Tapton Grove. The works were reconstructed in 1934, when they consisted of a top and low level works. They were further reconstructed in the mid 1950s, when an attendant’s house was built at the canal end. The reconstruction was due to the works being overloaded. Almost crude sewage was being discharged into the disused canal and was not easily diluted by the lack of water flow. It was later diverted into the river Rother. There were, particularly at times of hot weather, frequent issues regarding smells from the works, which eventually closed in 1990. The effluent is now pumped to the nearby sewage treatment works at Whittington. The site is now a housing development – centring on Windmill Way. It should be remembered that, right into the 1950s, the night soil man would be a regular sight in the village. It was his job to cart human waste from the privy middens, before the widespread provision of water closets.

For some years, particularly for the majority of the 20th century, the river Rother, which forms part of the parish boundary with Whittington, was the most polluted river in the UK. This was made worse by discharges from the Whittington sewage works (literally on the opposite side of the river from Brimington), which by the 1980s had downgraded the Rother downstream to ‘class 4 – bad’ – the worst classification. Partnership working, investment and closure of industry (therefore removing the worst of the polluters) has enabled to Rother to be improved so that it now forms a significant wildlife corridor. (Read more about the polluted river Rother in our blog).

Social history

Brimington Club, on High Street, can trace its origins back to February 1903, when a single storey brick and corrugated iron building was opened by CP Markham, managing director and chairman of the Staveley Coal and Iron Company. He handed over the building to two trustees, Brimington’s rector and the Staveley company’s general manager, for a nominal one shilling. An earlier attempt to establish a library on the same site had foundered. Markham stepped in paying for the new building and its contents – estimated at £1,200. Alcohol was served from the start, but in characteristic Markham fashion he threatened to ‘shut it up or burn it down’ if the club wasn’t administered properly. The building comprised a billiard room, library and reading room, and a bar area. In March the club had some 200 members, the committee having to refuse over 100 applications.

In 1905 a new brick structure replaced the old building, with improved facilities – twice the size of the old. There were now five principle rooms. In 1918 Markham conceived a plan which would have seen the club converted to a cottage hospital, with the then empty Brimington Hall becoming the club, but nothing came of this. A major extension was made in 1962, with major internal remodelling in 1974 (when it was said the club had some 4,000 members) and again in 1979. It was probably not until 1931 that the building actually became the property of the trustees. The club sadly closed, due to financial difficulties on new year’s eve 2024/early hours of 1 January 2025.

Established on John Street was a short-lived ‘Brimington Working Men’s Club and Institute’ – an entirely separate undertaking to the Brimington Club. It appears to have been established sometime around 1902-3 and officially dissolved in 1923, but may have ceased to function earlier. By 1942 the number 1082 Air Training Corps opened at their John Street premises, which has been the former working men’s club building or a replacement on the same site. In 1952 local councillor Walter Everett purchased the property on behalf of the local Labour Party, in whose ownership it remained until 2005. The Brimington Spiritualist Church leased the wooden building from the Labour party for their meetings. The site is now occupied by two houses – numbers 37A and 37B John Street. There is short history on the site available from our downloads page.

Brimington people

Brimington’s own hymn-tune composer Thomas Wallhead (d. 1928) had his work published in the former Wesleyan Methodist and the Primitive Methodist hymnals. His tunes included ‘Brimington’, ‘Whittington’ and ‘Sharon’, the latter last appeared in the 1938 Methodist Hymnal. He lived on the old Southmoor Road, now Manor Road, where his main occupation seems to have been as a music teacher.

You can find out more about Henry Bradley (the power behind the establishment of the Oxford English Dictionary) in an article on him available from our downloads page. He lived for a time on what is now Manor Road where his father was employed in a book-keeper’s role by John Knowles – the owner of the the iron smelting business there.

We’ve also published, jointly with two other local societies, a newsletter about Tapton House and George Stephenson. Visit our downloads page and look for the ‘George Stephenson and Tapton House publication’.

Finally, here’s Joe ‘ten goal’ Payne (1914-1975). A local lad, who lived in a house near the former Miners Arms public house on Manor Road. He still holds the record for scoring the most (10) goals in a single football league match. This was for Luton Town in their match against Bristol Rovers in April 1936. The photograph here is of him when playing for Chelsea. He also played for West Ham and was an England international. There was formerly a plaque on the front of the Miners Arms to commemorate Payne. This was removed in 2024.

If you have any information to add to any of the subjects above, or anything you think we might be interested in please contact us.

Page updated:

- 13 July 2023, when we added information to the sections on Brimington Hall, Tapton Grove, Thomas Beighton Ltd and the iron smelters and works on Manor Road.

- 26 August 2023, when we added links to our blogs on the Markham Arms and The Mill.

- 20 and 21 December 2023, when we added some information about Thomas Wallhead, the Umney family (rush matting makers), Henry Bradley, Brimington Hall, updated some links and reformatted some photographs.

- 17 October 2025, when we updated the public houses, Brimington Club and Joe Payne sections.

- 25 February 2026 when some illustrations were reformatted.