In this blog we’ll look at the Brimington and Chesterfield connection with the great Sheffield flood which occurred one hundred and sixty years ago on 11 March 1864.

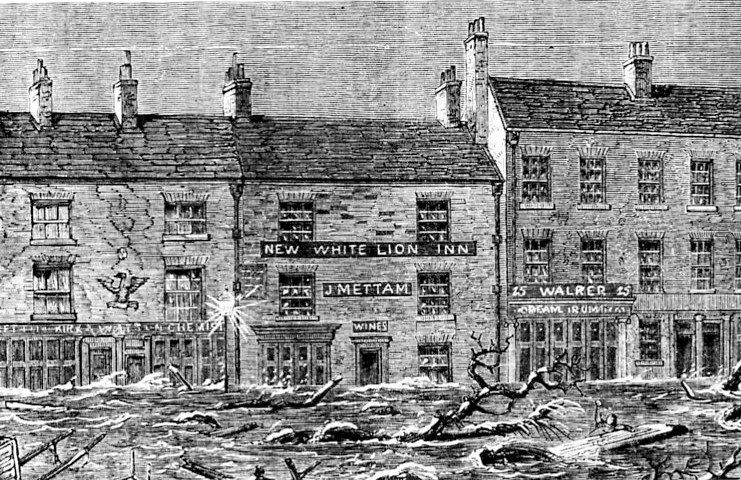

Sheffield suffered what became known as the ‘Great Inundation’ – when the nearly completed Dale Dyke Damn reservoir, around a mile from Bradfield, burst its banks. The resultant flood hit both the outskirts and nearer the centre of Sheffield and caused much destruction as houses, bridges, mills, businesses and other property were swept away. It is estimated that over 240 people and around 700 animals were killed.

This serious and sad inundation had a Brimington and Tapton connection as one of the three members of the inquiry held to apportion damages was Tapton Grove resident Mansfeld Foster Mills.

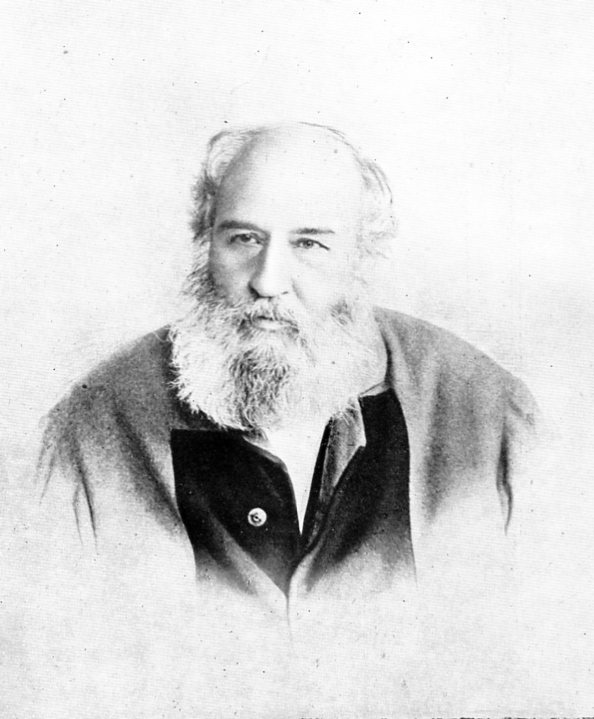

Mansfelt Foster Mills

Mansfelt Foster Mills (1821-1896) was one of three Inundation Commissioners appointed to assess damage claims – of which there were about 7,300. It may seem an odd choice, but Mills had risen to become a director of the Sheffield Banking Company and must have been well-known in the town. Indeed his background was in estate management.

Born in December 1821 in county Durham, Mills was a land agent and surveyor by profession. He came to Chesterfield as the agent to William Arkwright of Sutton Scarsdale Hall in 1841. He was one of the original 1853 partners in the Chesterfield Brewery Company, Brimington Road, being styled as managing partner. He was the second largest named shareholder in 1884 and a leading proponent of the Revolution House’s preservation. (The Chesterfield Brewery Company had premises that later formed part of the now demolished Trebor factory).

Mills was a director of the Sheffield banking Company from 1870 until he resigned, due to ill health, in 1886.

The Great Inundation

The private Sheffield Water Works Company had nearly competed their Dale Dike Reservoir, near Bradfield, which held around 691,000,000 gallons. Undertaking an inspection in the afternoon of Friday 11 March 1864, the resident engineer noticed that the reservoir’s water was being blown by wind straight up to and over its embankment. He remained unconcerned. Later, though, the situation had worsened. A water company employee whilst crossing the embankment saw a crack in its side. That evening the crack was examined and the incident heightened – with residents in nearby Lower Bradfield being advised of the danger. Later it appears that villagers were actually evacuating.

On another inspection, sometime after 10pm, it was found that the crack had widened. Efforts were then thought necessary to relive some of the water pressure on the dam by blowing up part of its weir, but these efforts were unsuccessful – the gunpower did not ignite. Shortly afterwards those trying to relieve the water pressure saw a 30 foot opening in the embankment, with water gushing through it – the start of a massive flood rolling down the valley, on its way into Sheffield. The embankment appears to have further given way, with the resultant gap some 110 yards long and 70ft deep. One might imagine the fear felt by those not expecting this inundation.

It appears the water reached the lower parts of Sheffield about 1am. The inundation was described as resembling one lake with the Wicker a boiling and foaming river. Its worst area was around Lady’s Bridge. An estimated 700 million gallons was said to have swept down the Loxley Valley.

Just like such tragedies today, many people visited the aftermath. It has been said that approximately 150,000 Sheffielders visited. So too did others from further afield, many coming by rail and using vehicles of every description. But for us locally, this did have one unintended positive consequence.

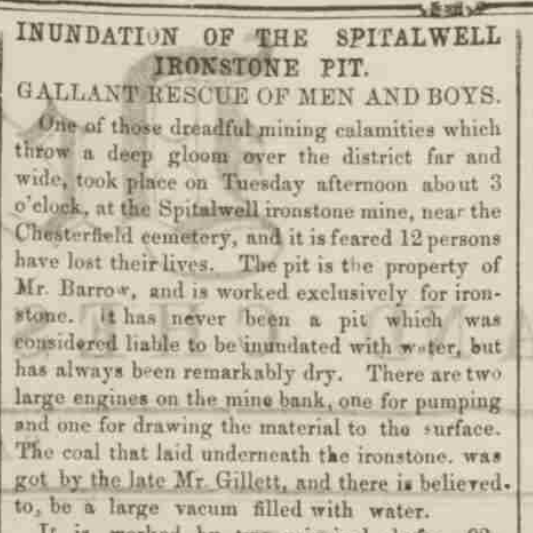

The inundation of the Spitalwell ironstone Mine

The seriousness of another, unconnected, inundation, was mitigated by the Sheffield disaster.

A few days after the Sheffield disaster – on 15 March 1864 – a serious water inundation occurred at the Spitalwell ironstone mine. This was situated somewhere off Piccadilly Road, Chesterfield. Water from an adjacent mine flooded Spitalwell, ultimately trapping 12 men. A brave and successful rescue was aided by RG Coke, a then well-known mining engineer. He lived at Tapton Grove from 1862 to 1879. It was said that, luckily, there weren’t more men at work due to them taking time off to visit the scene of the Sheffield flood.

Coincidently Coke formed a once well-known mine engineering business with one of the sons of MF Mills. Coke had probably been the tenant of Tapton Grove until it was purchased by the same MF Mills. Coke purchased Brimington Hall and went to love there for some years.

Connections

So, there are perhaps a few links to the Sheffield flood. One is a direct link with the owner and occupant of Tapton Grove – MF Mills. The other is with yet another occupant at the same property – RG Coke – and his leadership in successfully rescuing men trapped in another albeit unconnected inundation and this time underground. Here the rescue attempts were probably made easier as many more men weren’t working, due to them taking the day off to look at the aftermath of the Sheffield flood.

Sources used in this blog

G Amey, The collapse of the Dale Dyke Dam 1864, (1974).

J Hirst, Chesterfield Breweries (1991).

RE Leader, The Sheffield Banking Company Ltd. An historical sketch 1831-1916 (1916).

PL Scowcroft, ‘Excursion to disaster: Sheffield 1864’, Industrial Heritage, vol. 31, no. 1, Spring 2005.

D Williams, ‘The inundation of the Spitalwell Ironstone pit’, Bulletin of the Peak District Mines Historical Society, vol 11, number 6.

Various contemporary trade directories.

P Tuffley, ‘A disaster known as the Great Inundation’, Yorkshire Post, 24 February 2024.

Derbyshire Times, 19 March 1864.