At our September 2023 meeting we took a look at a number of local history subjects – one being how mains piped water arrived in Brimington. In this blog we take a brief look at this subject – an imperative need for all communities which we perhaps now take for granted until we turn on the tap and there’s no water!

What follows is a very brief chronology of water supply in the village up to the early years of the 20th century.

The story begins – 1825

The story begins with Chesterfield Water Works and Gas Light Company, which was created by an 1825 Act of Parliament. This enabled the newly created company to supply water and gas within the old borough of Chesterfield. But the old borough was not the one we now know – it then comprised the town centre, with a few surrounding areas. Brimington was certainly not supplied at this date – the populace relying on wells and pumps to supply their water.

The company extracted water from the newly dammed Holme Brook, about two miles to the west of Chesterfield. This was piped to what was then described as a ‘large reservoir’, which was formerly in the grounds of Reservoir House, West Street. This is the site of the county council’s West Street social services offices.

Gas works were built in 1826 at bottom of what was known as Pot House Lane (later Foljambe Road) m- the site of the Salvation Army building and Mecca Bingo. This site was then outside the borough as was the reservoir. The company was commercially successful.

1855 – reconstitution of the original company

In 1855 the old Chesterfield Waterworks and Gaslight Company was reconstituted under a new Act. This authorised construction of two new reservoirs;

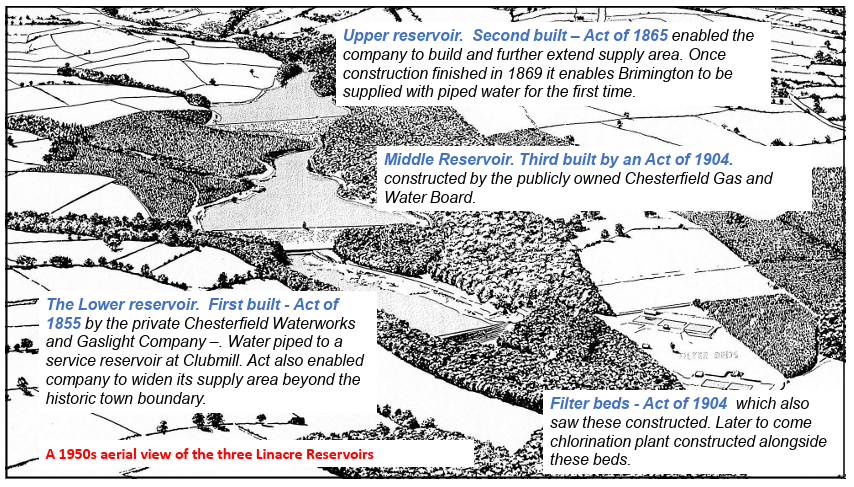

- The Linacre Lower Reservoir

- A second (smaller) reservoir at Clubmill in Newbold parish (nearer Chesterfield) – classed as a service reservoir.

Also authorised was a supply area extension into Brampton, Newbold, Walton, Tapton and Hasland, all outside but adjacent to the borough. Brimington was not included

1865 – foundations of a supply to the village.

Another Act of Parliament in 1865 conferred further powers on the existing company. It authorised an extension of their water supply area into Brimington and Whittington.

New works were also authorised including a second reservoir at Linacre – Upper Linacre Reservoir. Gas, though, could not be supplied to Whittington or Brimington without the consent the Whittington Gas Company. This company had already been set-up to supply gas to these to two areas – it had its works at the bottom of Whittington Hill.

The Chesterfield company had originally intended to extend its water supply area to Brimington, Whittington, Calow and Staveley, but failed to achieve powers to extend its network into the latter two communities.

The works begin

Works were begun as soon as the company was able to precede with these. The engineer was John Wignall Leather, with Thomas Hawskley consulting engineer to the company.

One of the stipulations of the Act of 1865 was that Brimington could not be supplied until the new Upper Linacre Reservoir was completed. But the works were not without problems. The first tender was invalid, an accident polluted water in the existing reservoir and there were engineering delays – including some concerns about the dam wall moving. Despite these, in 1869 the reservoir was complete and nearly full of water in March of that year.

1869 – Water finally arrives in the village

As mentioned earlier, the 1865 Act stipulated water could not be supplied to Brimington until Upper Linacre reservoir was complete.

We can be fairly certain that the company was near to supplying water to village customers in the spring of 1869. That’s around the time that the reservoir was described as nearly full. In the same period we have also have a short series of letters from Charles Markham of Brimington Hall, expressing concern about delays by the company in connecting up their new main to his property .

Water – but only if you could afford it

Piped water from Linacre arrived to the village in the spring of 1869 – but was only available to those who could afford it – and people in the parish paid more for it than those in Chesterfield. Nor was it guaranteed as constant in all areas.

The company’s main to Brimington was via a new pipe connecting with their existing pipe on Sheffield Road, at the junction with Pottery Lane. It then ran along Brimington Road North, Wheeldon Mill, Devonshire Street, to Church Street and along Ringwood Road. It finished at one of the entrance lodges to Ringwood Hall, which are actually just outside of the parish. This arrangement caused many issues with supply interruptions as the system relied on the natural water pressure – it was not pumped. The height of the service reservoir at Clubmill (which was later abandoned presumably due to subsidence) was also slightly lower than the majority of properties on Brimington Common and there was no compulsion for the company to provide a constant supply to properties above this level.

The company’s supplies were not filtered or treated in any way – something that we perhaps find hard to imagine today. There were numerous reports of debris in the water including vegetable matter, bits of fish and newts, along with poor odour, particularly at times of water shortage.

As a consequence of all this some people in Brimington, particularly along Brimington Common, still had to rely on wells which were at risk of pollution.

An unpopular company

It is probably fair to say that whilst the company was commercially successful, it was not well regarded in the district.

There were numerous disagreements with Chesterfield Corporation over supply issues and pricing. Included was a serious disagreement in 1881 when the corporation refused to pay for high gas charges. Electric street-lighting was instituted as a result of this until 1884 – resulting in the town having (with Godalming in Surrey) the first installation of public street lighting in the country. High gas and water charges were an issue for many years. Then there was the already described shortages, poor quality and lack of constant water supplies. Not surprisingly there were increasing calls improvements, including public ownership.

Trouble and a solution

The end of the company was sealed in 1893. In an effort to address water shortages the company applied for an Act to dam the River Hipper at Holymoorside, to raise capital by £100,000 and increase water charges. The Hipper proposals caused much opposition from local industrialists (concerned at the loss of water flow in the river), residents and local authorities. When the Bill went to committee stage in parliament a flow of witnesses from the district appeared giving evidence against the company. The Bill was not proved, with permission given to Chesterfield Corporation and the two urban district councils of Whittington and Newbold (as a joint board) to apply for an Act to take control of the undertaking.

In 1895 the Gas and Water Board Act for the borough of Chesterfield and adjacent districts was passed. The Chesterfield water and gas works passed to the board. Works were instituted to modernise the system, with excessive leaks tackled.

Linacre Middle Reservoir and filter beds were constructed following an Act of 1904, with a later water chlorination plant built adjacent.

Our story ends for now

At this stage, our brief story of water in Brimington ends. But there were still issues with poor supply pressure to Brimington Common, which was only resolved some years later, with further capital works by the board, corporation and later successor water boards required to address this.

Some pertinent quotes – 1 – no water to a house in Brimington in 1878

The Chairman [of the rural sanitary authority]

‘thought a good supply of water was necessary at Brimington if it was only that they might wash their houses.—Another Member: “And their faces.” (Laughter.)—After some further conversation the subject dropped.’

Derbyshire Courier and Derbyshire Times, 2 March 1878

Some pertinent quotes – 2 – the ‘water famine of 1893’

Doctor Barwise the County Medical Officer of Health reports:

‘People were obliged to drink rain water and water from the surface wells’

Children at Brimington Common were reported as drinking dirty water from washing bowls at the Board schools.

Derbyshire Times, 2 December 1893

Barwise later commented:

‘The taps were there but there was no water, I tried them… It was a serious drought—the sort of thing one reads of in the desert…I do not think it is a very common thing for people to be actually thirsting for want of water?—It was certainly an exceptional experience to me.’

House of Commons, Select committee on private Bills, Chesterfield Water and Gas Bill, 1894

This account has been condensed from a much fuller account of how mains water reached the village, which we hope to publish in a forthcoming edition of our yearly history review ‘Brimington and Tapton Miscellany’ in which all sources will be fully referenced.