Ringwood Hall is not in Brimington (though many think it is and the address is mostly given as Brimington). So, for this blog we’ve strayed a little beyond our normal Brimington/Tapton area to present this brief history of the hotel.

Some time ago we said that it might be handy to resurrect the short history of Ringwood Hall written by Sandra Struggles, which formerly appeared on the hotel’s website. In fact we’ve gone one better and revisited her short history, that of Kay O’Flahery’s 1998 ‘Ringwood Hall: its history and occupancy’ and of Cliff William’s ‘GHB and Ringwood Hall’ article in the North East Derbyshire Industrial Archaeology Society’s newsletter, August 2009 (reprinted in 2018). Generally, though, it’s the latter that forms the basis of this chronological history, particularly up to the Second World War years. Our thanks, then, to Cliff Williams for allowing us to use his research undertaken over many years, particularly in the archives at Chatsworth.

This research has also been supplemented with a trawl through the British Newspaper Archive. We have only added a representative selection of events held at Ringwood Hall, covered in local newspapers, accessible via this useful resource. Doubtless there are many others to be found which will fill in other details about the history of Ringwood Hall.

Chronology of Ringwood Hall

Note: Ringwood Hall is not an ancient manor house. It was built firstly as a residence for George Hodgkinson Barrow – who we will call GHB in this account.

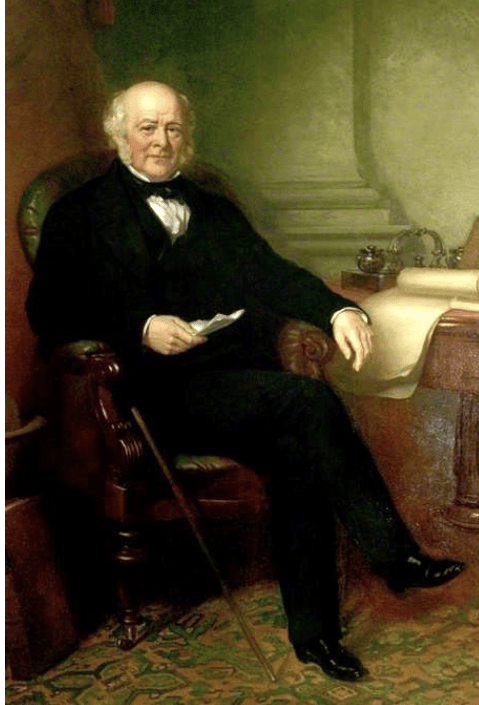

1815 – GHB takes over the ground leases of the Staveley forge and ironworks from the Duke of Devonshire as the sole proprietor. Barrow’s family home was at Southwell, where he was a solicitor. (The family has been traced back to yeomen farmers in Westmorland and adjoining parts of Yorkshire and Cumberland. For details about the family, including some references to Staveley see Nicholas Kingsley’s website here).

1818 – GHB negotiates his first coal leases.

By 1820 – GHB is working the forge, ironworks and six different ironstone pits in the Staveley area.

1829 – GHB decides to build what became known as Ringwood Hall.

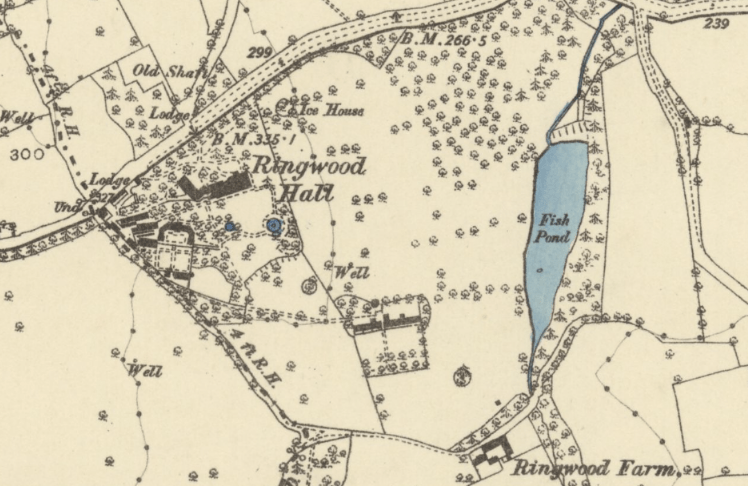

1830 – Ringwood Hall built and complete by September. Designed in a Regency style the architect is unknown.

1831 – Lease signed between GHB and the Duke of Devonshire for Ringwood. (It appears that a delay in signing this had occurred due to costs incurred in erecting the new mansion. Until GHB moved in it is likely that initially he had visited the works from Southwell. In the early years he possibly stayed at was termed the Jacobean House (now demolished) in the works area and then may have stayed more extensively at Staveley Hall Farm).

GHB had to keep Ringwood Hall in good order. His lease required him to paint all the outside wood and iron work with two coats of ‘oil colour’ every four years).

1840 – GHB renews his lease on the Staveley properties, ironworks, etc. with the Duke of Devonshire.

1841 – Census: GHB, his wife, two daughters and servants at Ringwood Hall.

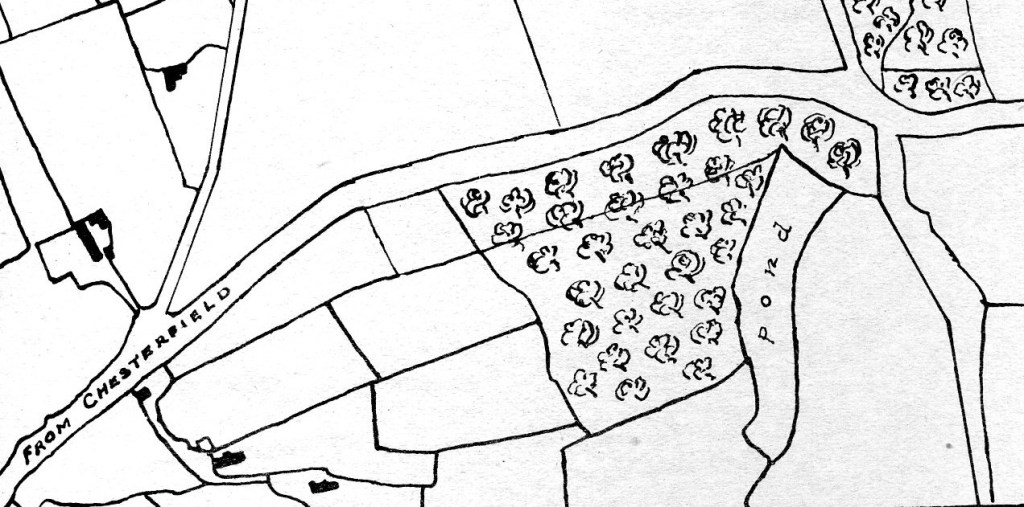

1841 – Tithe Award – GHB tenant – Duke of Devonshire owner of the property.

1843 – GHB surrenders his Staveley lease to his younger brother Richard – an experienced and wealthy merchant – who takes control of the business.

1846 – An assessment of the duke of Devonshire’s property held by GHB includes Ringwood Hall and outbuildings, ornamental plantation, gardens and pleasure grounds, kitchen garden. Also included were a stone thatched cottage with yard, garden and croft and Nethercroft field. All were leased on a year-by-year basis of £35 rent – totalling just over 36 acres.

1853 – Death of GHB. Richard Barrow is living in Ringwood Hall.

1853-1857 – Richard begins to improve and extend the Hall, grounds, and gardens. Accounts analysed by Cliff Williams at Chatsworth show that thousands of bricks were used in the work.

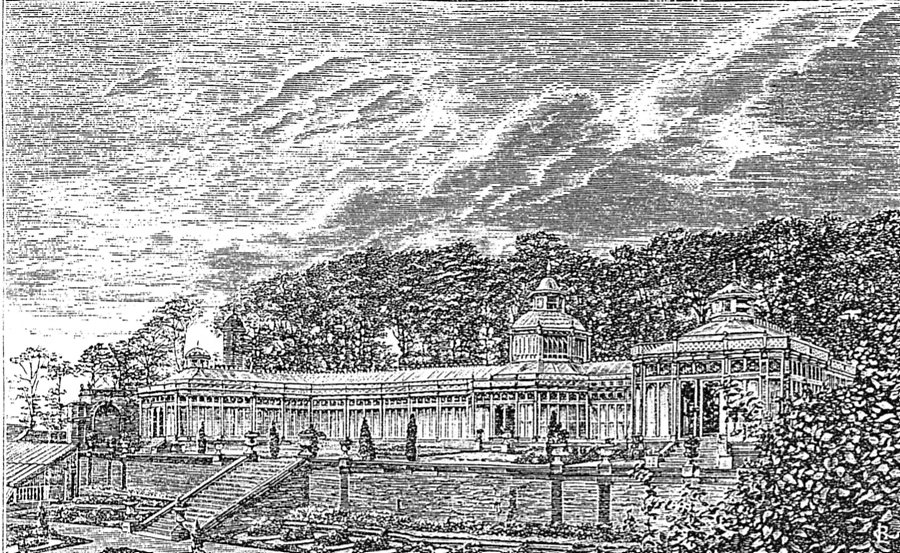

1856 – In November Richard opens the grounds at Ringwood, including a recently erected cast iron and glass conservatory, to his employees and their families. (Unfortunately, no documentary evidence has been found to substantiate the local tradition that Joseph Paxton had a hand in the conservatory’s design).

1857 – Richard renews the lease on Ringwood with the Duke of Devonshire, for a term of 99 years at £100 rent per year. The inside of the property now had to be redecorated every seven years, but the other (1831) covenants remained the same.

1850s and 1860s – During the period Ringwood Hall’s gardens were opened on Sundays to the families of employees (according to Stanley Chapman’s book on Stanton and Staveley).

1863 – The Staveley industrial concern is one of the earliest companies to be incorporated. At this date it appears that Richard Barrow fully owned the Ringwood Hall and its estate as it was not included in a land exchange between the new company and the duke of Devonshire.

1865 – Death of Richard Barrow. He is succeeded at Ringwood by his brother John, who had been his partner in the merchant trade. Richard had owed some £260,000 to his brother John, of which £100,00 was invested in the Staveley company. John was appointed the next Chairman of the Staveley company.

1871 – Census records a head gardener and five gardeners at Ringwood Lodge and in two garden bothies. Charles and Elizabeth Boyer is head of household – she was the daughter of GHB, with full retinue of domestic staff, housekeeper, etc. About this time John Barrow had been advised to move to London due to his deteriorating health.

1871 (22 July) – John Barrow dies at his London town house – 85 Westbourne Terrace, Hyde Park. He was 82.

1871 (August) – John James Barrow, another nephew of Richard is resident at Ringwood Hall.

1872 (July) – Ringwood Hall opened for the annual works horticultural show.

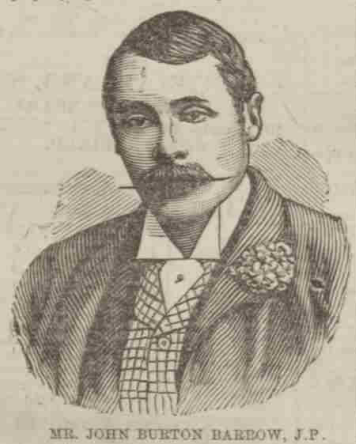

1875 – John James Barrow moved from Ringwood Hall to Tunbridge Wells (where he died in 1903). He was the last of the founder directors. The next incumbent appears to have been John Burton Barrow, JP, a barrister and yet another of Richard’s nephews.

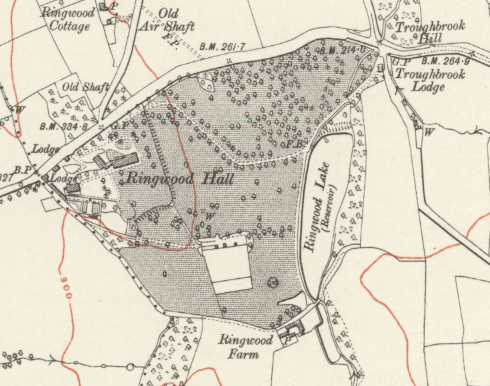

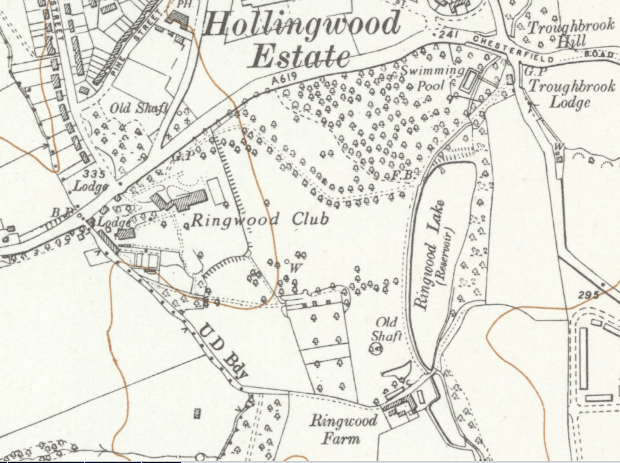

1875 – Ordnance Survey maps shows a lodge to the top of Private Drive, Hollingwood. (Apparently Private Drive (a name this road still retains) was formerly a private drive used by the Barrows to reach the works at Staveley from Ringwood Hall).

1876 – The ‘Journal of Horticulture and Cottage Gardener’ for March published a comprehensive report on the hall’s gardens, conservatories and glass houses. It states that Richard Barrow had been responsible for these, under the superintendence of head gardener Mr Petch. Mentioned is a fountain within the largest conservatory – which was later presented to and erected in Hasland Park by CP Markham.

1880 – The Rufford Hounds meet at Ringwood Hall, courtesy of JB Barrow.

1881 – Census has no record of head of household occupants at Ringwood Hall, but it is likely that this is a result of John Burton Barrow’s move to Southwell, for a short period. His third child was born at Ringwood in 1881.

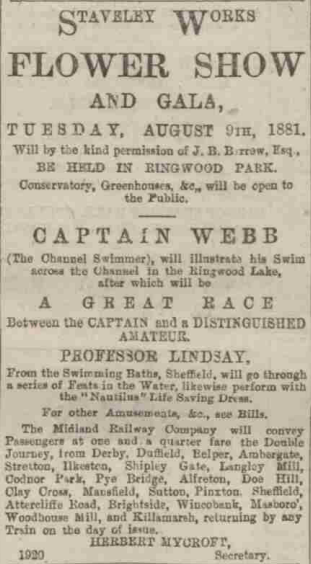

1881 – Captain Webb, the famous English Channel swimmer, swims in Ringwood Lake as part of the Staveley Works Flower Show and Gala, held by courtesy of JB Barrow.

1887 (January) – Skating on the lake at Ringwood.

1890 – April The Derbyshire Times of Saturday 26 April 1890 reports that representatives from the Unionist party in the North Eastern (Eckington) division had been to see JB Barrow at Ringwood Hall and was announced that Barrow would stand as a Unionist candidate for the division, as a prospective MP. The Conservative leaning newspaper waxed lyrical about Barrow as; ‘probably, [the] best all round man they could have wished for sound, pleasing and outspoken speaker, a genuine, conscientious politician, hearty good fellow personally, and the representative of a family which has devoted immense capital and great abilities to the establishment and development of industries which have found work and wages for thousands, and for years. Mr. Barrow has also the further recommendation of being accessible, and he does not, like his rival, drop down for a few minutes occasionally and leave nothing but empty words and emptier promises, but he lives in, and for the district in which his great interests are contained.’ Barrow had unsuccessfully contested Mid-Derbyshire in 1885 and the South Notts seat.

1890 – October. Perhaps typical of the period the Derbyshire Times of Wednesday 26 November 1890 reports; ‘On Thursday, J. B. Barrow, Esq., Ringwood Hall, and seven guns, shot over his estate. The bag included 56 pheasants, 74 rabbits, eight hares, one brace of partridges, and five woodcocks. The guns were Mr. J. B. Barrow, Mr. Richard Barrow, Mr. Leonard Barrow, Mr. Milner (Totley Hall), Mr. C. P. Markham, Mr. W. H. Newman and another gentleman. Mr. Barrow is known as one of the best shots in the Midlands, although he uses very small bore gun’.

1891 – John Burton Barrow appointed to the Staveley company board and the Manchester Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway board. (Alongside his Staveley interests Barrow was also a director of the Amsterdam Hill Waterworks Co. (which supplied the City of Amsterdam with drinking water) and a director of the Pembroke and Tenby Railway Company).

1891 – The census identifies the family at Ringwood Hall, along with a large complement of staff. Two lodges are recorded in the grounds. The total number of residents in the hall on census night was 21 – with 24 combined bed and dressing rooms.

1891 – April. JB Barrow resigns as parliamentary candidate for North East Derbyshire on health grounds.

1891 – July. Staveley works flower show and gala at Ringwood Hall.

1891 – October 8th, 1891. The whole of the ‘stove and greenhouse plants’ are for sale by auction on instructions of JB Barrow. The reason for sale is not clear and perhaps warrants further research.

1892 – In June of the annual Staveley works horticultural show is being held at Ringwood with his permission.

1893 – Barrow is still being described as of Ringwood Hall at least until February.

1894 (October) – The Marquis Piedilemine de Saliceto moved into Ringwood from Garenden Park, Leicester. John Burton Barrow and his family having previously moved out.

1894 – Staveley Horticultural Society Show held again in the grounds of Ringwood Hall, hosted by Piedilemine de Saliceto. There had been many previously held such shows in the grounds.

1895 – Piedilemine de Saliceto had moved out of Ringwood Hall. He is declared bankrupt the following year.

1896 – Contents of Ringwood Hall for sale, including ‘a valuable cellar of wine, included a bin of the celebrated Port known as the “Ringwood Port” of 1824 and 1847’.

1898 – Ordnance Survey map denotes Ringwood lake as a reservoir.

1899 – Ringwood Hall for sale by auction. Described as set in about 110 acres, with ‘well-timbered’ park and ornamental lake. Despite several bids the property was unsold at £14,250. It is thought the vendor was probably John James Barrow of Tunbridge Wells.

1899 – The sale details of this year include reference to the Ringwood lake as being in use as a reservoir for the Great Central Railway. Water is piped down the valley to the railway line and thence to the railway’s engine sheds near Staveley Lowgates.

1899 – Ordnance Survey map shows the large conservatory as still present.

1900 – Thomas Bayley gives his address as Ringwood Hall in parliamentary election correspondence. He is elected as MP (Liberal party) from the Chesterfield Division in the elections of October 1900.

1901 – Census; Ringwood Hall is uninhabited. Three gardeners, a coachman, but no domestic staff recorded as resident. Perhaps the occupant – Thomas Bayley – is not present as he is on parliamentary business.

1902 – About 160 members of the Brimington Women’s Liberal Association ‘entertained to tea’ at Ringwood Hall, in a marquee, by Miss Bayley (d. 1921 – Thomas Bayley’s sister). On a second occasion members of the Chesterfield branch also entertained similarly. There are references to other Liberal party organisation gatherings at Ringwood Hall during this period.

1904 – Advertisement in the Derbyshire Times, 13 February 1904 – Ringwood Hall to be sold or let unfurnished

1907 – Charles Paxton Markham purchases Ringwood Hall (presumably following the death of John James Barrow in Tunbridge Wells in 1905). The Derbyshire Times in reporting the sale states (26 January) that the house is occupied by WBM Jackson.

1908 – Kelly’s directory of Derbyshire has William Birkenhead Mather Jackson at Ringwood Hall. He would have moved from Clay Cross. (The Jacksons are closely associated with the Clay Cross Company. Markham’s first wife was also a Jackson). This appears to have been a short-lived occupancy as during the year CP Markham apparently carried out improvements and renovations at Ringwood Hall. Markham moved in from Hasland Hall, in the same year. Other evidence has the date of his move as 1911 (see below).

1909 – Chesterfield and District Chrysanthemum Society spring show at Ringwood, the residence of Mr WBM Jackson. Includes a football competition and gymnastic display by the Brimington Athletic club and ‘dancing in the evening’. The Dronfield Town Band were in attendance. (During the period up to the handing over of the Hall to the Staveley Coal and Iron Company, events such as this were not unusual).

1911 – Excerpts from a letter by CL Hazzard (CP Markham’s gardener) in Kay O’Flaherty’s 1998 account of Ringwood Hall quote him as saying, on his arrival in 1911, that the gardens were a ‘wilderness’ with the grass not cut for a year. During this period to 1916 (when he left) Hazzard knew of many improvements carried out including construction of a flagged garden, the gardens and house remodelled, with flowering shrubs planted around the lake

1913-14 – Middle Lodge constructed. Markham has inscription ‘Fools build houses for wise men to dwell therein’ cut into the stonework above the front door.

1913 – Fountain believed to have been originally situated in the large conservatory, presented by CP Markham to Eastwood Park, on that park’s opening. (The fountain is still there, despite being moved to Chesterfield town centre in the 1980s).

1915 – Brimington parish church Sunday School treat held in the grounds of Ringwood Hall.

1921 – Ordnance Survey map showing no traces of the large conservatory. Local tradition has it that it was demolished following a severe storm.

1925 – CP Markham marries for the second time – Francis Marjorie Nunnely – following an acrimonious and very public divorce. (Mrs Nunnely had lost her husband in the First World War and was the mother of two sons).

1925 – Markham’s former wife makes claim that some of the furniture at Ringwood is rightly hers.

1926 (29 June) – Markham dies, in his car, having suffered a heart attack in the grounds of Ringwood Hall.

1926 – Markham’s second wife hands over Ringwood Hall for the use of staff (i.e. salaried employees, not those hourly paid) as a club. She went to live at Guilsborough Hall, in Northamptonshire.

1926 – In August of this year some 50,000 people are said to have visited the Ringwood gala and musical fete, organised by the late CP Markham.

1927 (May) – Ringwood Hall opens as a club.

(As recounted below, Ringwood Hall survives various company amalgamations, nationalisation and resale back into the private sector, as a club, until 1988. It was once quite well-known for its dinner and dances, Italianate gardens and bowling green. Galas and shows in the grounds were a feature for many years afterwards. For a time the house was also used for board meetings of the Staveley company).

1944 – Ringwood Hall reportedly left in a poor condition following the Second World War years which prompted the need for refurbishments. Club membership during this period was relaxed to include non-salaried staff.

1947 – Coal mining industry nationalised. It is not known how this impacted upon the membership of the club, as presumably those staff members from the coal side of the Staveley company’s business might not now be eligible to join it.

c.1947 – Despite the reported poor condition of the club in 1944 (above), the Staveley Iron & Chemical Company in their Staveley Story (of about 1947/1948) describe Ringwood as ‘… a great club and playground for the employees of the Staveley Company, with its noble mansion as a splendid social centre.’

1948 – Ringwood park compulsory purchased by Staveley Urban District Council, following failure to agree terms with the Staveley company.

1950 – Ringwood Lake reservoir spillway reconstructed by British Railways.

1951-1952 – RS Beavor in his book Steam was my calling notes that one of his duties when shed-master at Staveley Central locomotive shed was to visit the Ringwood Lake reservoir.

1960s – Ringwood Hall becomes well-known for its Saturday evening and seasonal dinner dances.

1960 – Stanton and Staveley amalgamated this year. The combined business was firstly under the control of the Stewarts & Lloyds then later the British Steel Corporation. (Staveley employees generally thought that their part of the company was seen as second best to Stanton after this amalgamation).

1983 – The Derbyshire Times of 4 February reports on the annual meeting of Ringwood Club members, where it was announced that the club is secure. Members had feared the cost of running and maintaining the building might lead to closure. The building is still owned by Stanton & Staveley Ltd.

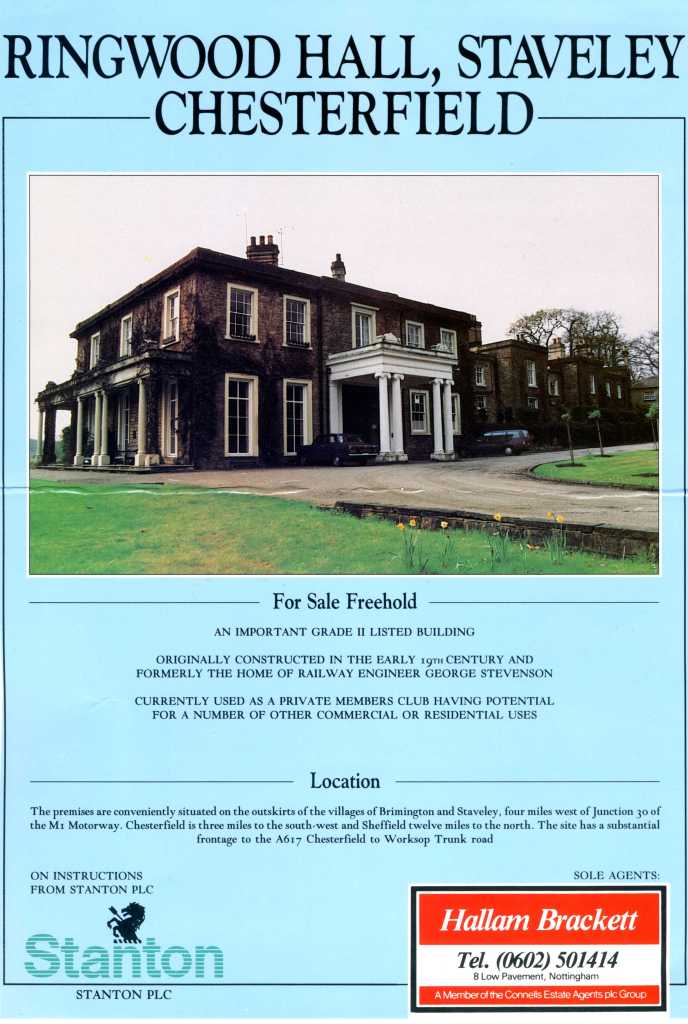

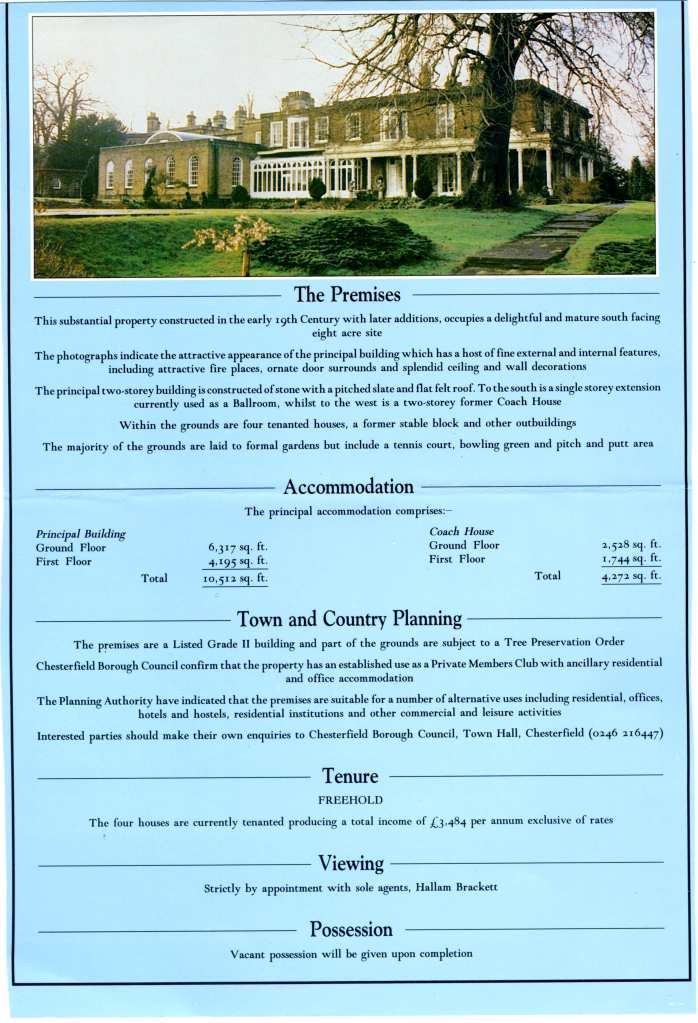

1988 – Stanton plc sell Ringwood Hall for an undisclosed sum to Bill Hiscox and Susan Hobson. The latter spend a considerable sum of money renovating and improving the property, but reportedly sell it to avoid bankruptcy.

1998 – ‘Touchstone’ charity start efforts to reclaim the kitchen gardens, which were in state of neglect. Includes erection of new greenhouse frames on remains of former Victorian bases.

2000 – Purchased by Lyric Hotels, after being in a number of hands including Mr M McDonald (1995) and Classicrange Hotels’. They still (as at 2023) own the hotel.

2002 – New health and fitness centre opened at the hotel.

2018 – New spa facility – ‘The Garden Secret Spa’ – opened.

2018 – Chesterfield and District Civic Society ‘Blue Plaque’ erected in entrance porch to Ringwood Hall. Commemorates both the hall and it being the home of CP Markham.

2021 – The kitchen garden is once again in a state of neglect. A planning application to extend the hotel’s spa into this area is made.

2023 – The hotel’s website says that ‘Ringwood Hotel & Spa is a beautiful 19th century manor house hotel. Set amongst 6 acres of formal award-winning gardens, the Grade 2 listed hotel is surrounded by 29 acres of parkland’. The hotel is not, however, a ‘manor house’.

Sources used in this blog

The principal source for this blog is Cliff William’s article cited below. We are very grateful to Cliff for permission to use his research in this blog.

C Williams, ‘GHD and Ringwood Hall’, North East Derbyshire Industrial Archaeology Society (NEDIAS) Newsletter, number 25, August 2009. Cliff was able to make use of his extensive work at the Chatsworth archives in this account. (Reprinted in NEDIAS newsletter number 69 – February 2018)

K O’Flahery, Ringwood Hall: its history and occupancy’ (1998). (A copy is in Chesterfield Local Studies Library).

Other sources

S Struggles ‘Ringwood Hotel – History’ [On Line] at URL http://www.lyrichotels.co.uk/ring/index.htm last visited 27 NOV 2004 (not now present).

P Cousins, ‘Water for steam engines from the Chesterfield Canal, Brimington and Tapton Miscellany, 7, 2015.

RS Beavor, Steam was my calling (1974).

The Staveley Iron and Chemical Company, The Staveley story (no date, but c. 1947).

S Chapman, Stanton and Staveley: a business history (1981).

Various Ringwood Hall hotel brochures.

Contemporary newspaper reports.

This post was slightly edited on 14 June 2023 to add a close-up copy of the 1921 Ordnance Survey map of Ringwood Hall and on 20 June 2023 to remove an incorrect reference to John James Barrow being a nephew of John Barrow – he was not. It was further edited on 16 July 2023 to add more information for 1890 and on JB Barrow. Information for 1983 was added on 29 July 2023.

In 1913 C.P.Markham donated the fountain that now stands in EASTWOOD Park that once adorned the entrance to Ringwood Hall,Today it is a flower/Rose bed In the 1980s the local council removed it to Low Street Chesterfield and during the renovations of EASTWOOD Park 2013? it was returned to where C.P.Marckham had requested..

Sent from Mailhttps://go.microsoft.com/fwlink/?LinkId=550986 for Windows

LikeLike

I’m not sure whether it was at the entrance to Ringwood Hall originally. I think it was in the conservatory. It would be interesting to try and trace where it was situated after the conservatory at Ringwood was demolished. Perhaps it was then situated at the entrance to Ringwood Hall, then went to Hasland when the park opened.

LikeLike

No reference in the chronology that the Hall was formerly the home of George Stevenson?

LikeLike

There is no reference in the chronology body text to ‘George Stevenson’ having lived at Ringwood Hall as there is no documentary evidence whatsoever to George Stephenson (the ‘father’ of the railways) having lived there. There is a comment about this in the text caption to the 1980s sale details illustrations. George Stephenson’s home in Chesterfield was Tapton House, not Ringwood Hall. Where the notion of Stephenson having lived at Ringwood Hall comes from is unknown, but, as far as I am aware, it has no basis in fact. The first mention of it (complete with incorrect surname spelling) is in the 1980s sale details – but this is not grounded in documentary evidence. This doesn’t, of course, mean that he didn’t visit Ringwood Hall, (along with other residences of the same ilk (e.g. Tapton Grove), during his time in the area.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your corroboration Philip. I did wonder!

LikeLike