In this blog we will start to look at the claim that victims of the plague were buried near the canal off Cowplingle Lane – a tradition almost certainly incorrect.

This is part one of a series of blogs which look at the plague in Brimington which visited from late 1603 to early 1604.

The plague visits

Nine people are recorded as dying of the plague in Brimington, from late 1603 to early 1604, but there were perhaps two other victims.

According to a well-known antiquarian and one-time rector of Whittington – The Rev Dr Pegge – during the outbreak villagers took two measures to isolate themselves from the surrounding area. They constructed cabins for the sick in remote fields to the north of the village. A bridge connecting the parish with nearby Whittington was also demolished. As a result of these measures (effectively the population insolating itself to some degree) the plague did not appear to spread elsewhere and deaths were minimised.

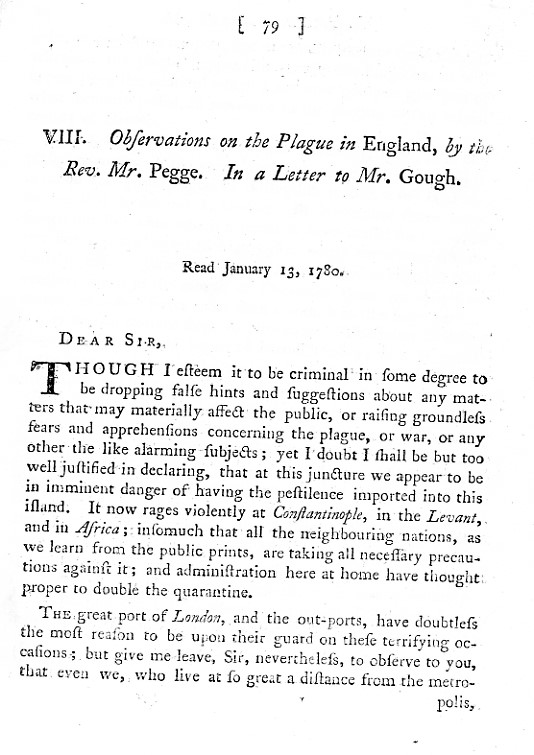

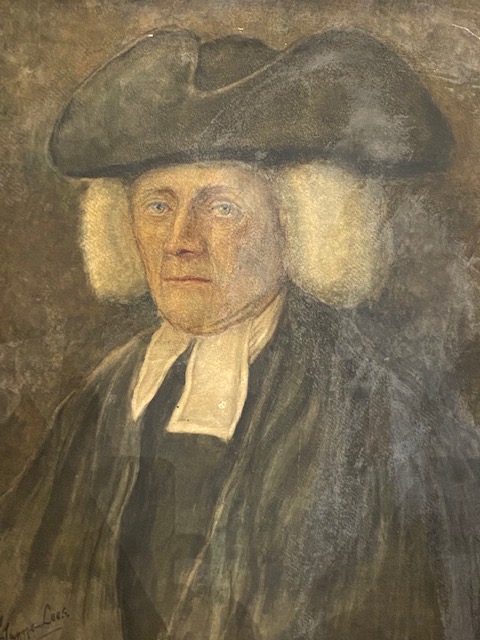

Pegge (1704-1796), saw a letter from him to a Mr Gough, of January 1780 published entitled ‘Observations of the Plague in England’. Pegge was Rector of Whittington for 45 years, so knew the area well. It should be noted, however, that the plague visited Brimington for a few months in 1603-1604, so his account was actually written some 170 years after the event!

Pegge didn’t just write about the plague in Brimington, but elsewhere, including Chesterfield. He states that the town was visited by the plague in 1586 (until 1587) and again from March 1609. It’s Pegge’s account on which the story of the plague in Brimington appears to have been almost wholly based (or in some quarters later misinterpreted).

Amongst other things Pegge in his ‘Observations…’ states:

- It was uncertain where the plague in Brimington had come from (but it probabaly came from London)

- It appeared at ‘Brimington at the end of October 1603, between which time and January 2 following there died, at this small place, and were there buried, five men and four women, as appears from the parish register of Chesterfield.’

- It didn’t spread elsewhere due to measures taken to isolate the village.

Crucially for our story Pegge writes in his letter to Dr Gough;

The measures pursued by the inhabitants of Brimington among themselves are only known by tradition, which informs that some cabins were erected in a field there now called from thence Cabbin-field.

Archaeologia, Volume 6, 1782, pp. 80-81.

Pegge does not state that there were any actual burials at Cabbin-field.

Chesterfield parish church registers record the plague

Burials, baptisms and marriages at the time of the plague in Brimington are noted in the Chesterfield Parish Register. At that time Brimington was a Chapelry of Chesterfield. There was a chapel building on the site of the present parish church, with a burial ground.

The Chesterfield parish church registers list plague burials beginning with Elizabeth Massie on 31 October 1603 who ‘died (as it was thought) of the plague and was buried at Brimington’. The November 1603 register begins with an ominous note ‘Plague at Brimington’. Mercifully the last burials were on the 2nd January 1604 of two further Brimington plague deaths and burials. All these burials are record as being at Brimington.

In retrospect it might well be possible to identify two earlier victims of the plague. Though these are not so defined in the register. So, there appear to have been a maximum of 11, with perhaps nine confirmed – the latter number used by Pegge.

But there does remain a mystery. It’s recorded in the Chesterfield parish church registers that the known victims were buried ‘at Brimington’. Why this distinction is made, when it is not normal to see other burials at Brimington recorded is unknown (possibly it was more normal for burials to be in the Chesterfield church-yard). These plague burials, however, would undoubtedly have occurred in the Brimington Chapel burial ground – again there is no evidence that burials occurred outside of consecrated ground. It must also be assumed that residents would be very reluctant to be buried in such unconsecrated ground.

At Eyam it is known that the plague victims there (it visited from 1665-66) were buried outside consecrated ground and that formal funerals were abandoned. This was, however, in reaction to some months of the plague’s presence in the village and many more deaths than that in Brimington. It has also been documented that at other places burials were undertaken outside of local burial grounds.

No evidence for Cabbin Close burials

Pegge does not say that anyone was actually buried in the fields where the cabins had been erected. One might have expected that a rector of an adjoining parish would have mentioned this if the tradition of plague burials outside of the consecrated ground of Brimington Chapel had occurred. But Pegge does not. As Pegge was rector at Whittington when the Chesterfield Canal cut through the field during its construction, presumably he would have soon got to know if any evidence of actual burial remains were discovered. Therefore, we may conclude that in Pegge’s account there is no evidence that anyone was actually buried at the site of the cabins.

Where was Cabbin Close?

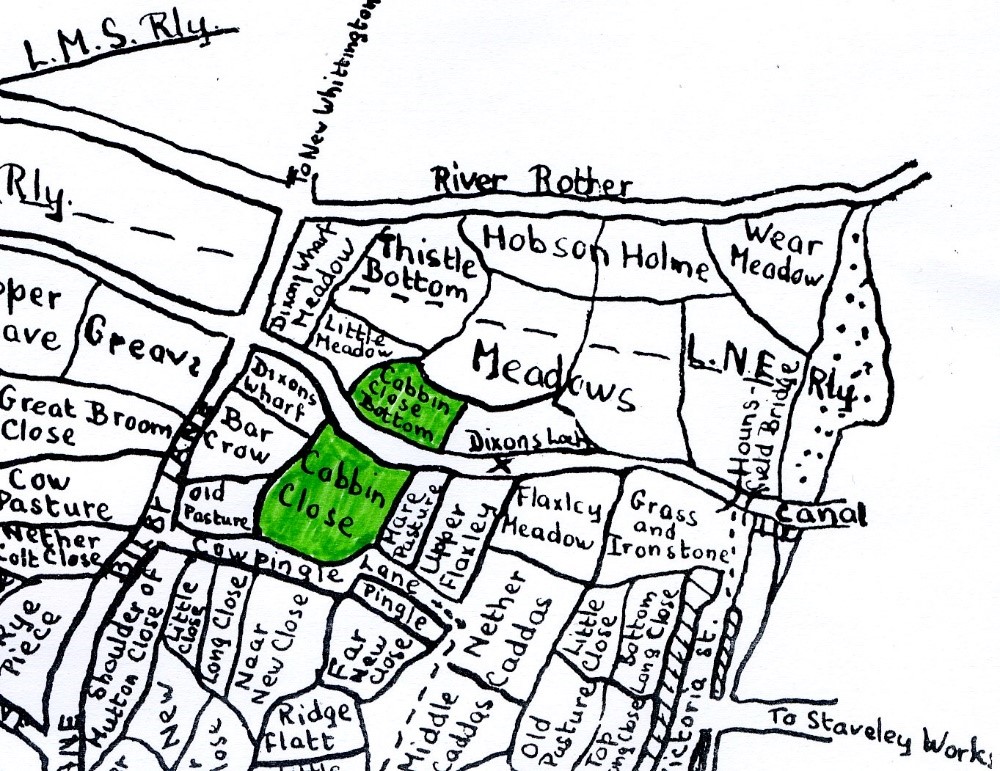

The name ‘Cabbin-field’ presumably came from cabins that were erected to house those suffering the plague, as stated by Dr Pegge in his 1780 account.

The ‘Cabbin-field’ name appears to have morphed slightly into Cabin Close or Cabbin Close, which, as discussed, was cut through by the Chesterfield Canal during its construction in the 1770s. Cabbin Close Bottom is north of the intersecting canal; Cabbin Close is south of the canal, off Cowpingle Lane.

We find that the fields are recorded in 1827 as ‘Cabbin Close’ (5 acres 1 rood and 25 perches) with ‘Cabbin Close bottom’ (3a 3r 2p) and subsequently so in the Tithe Award and Enclosure Award, both of similar dates in the 1840s (though the Enclosure Ward had ‘Cabin …’). In the 1840s tithe award Cabin Close bottom is described as grassed, whilst Cabin Close is ‘arable’ – i.e. under cultivation.

Our next blog

In our next blog we’ll explore a little further where the almost certainly incorrect notion of actual plague burials in Cabin Close fields came from.

We’ll explore that this notion probably dates from misinterpretation’s of Pegge’s account of the 1780s, via published parish histories in the 1920s and the 1930s and, more recently, incorrect claims about the burials, which were made in the 1980s and are perpetuated today in official lists of the site.

We’ll also look at the subsequent history of the area (which includes it being subjected to opencasting and other ground disturbance). In our final part we’ll look at the demolition of Goose-Acre Bridge.

Part 2 of this series can be found here.

A much fuller article on the plague in Brimington will be published in our Brimington and Tapton Miscellany later in 2023, but we’ll list the sources we have used in this series of blogs in our last part.

This account is edited from ‘The plaque in Brimington (1603-1604) part 1 – were there plague burials at Cowpingle Lane?’ That account appears in our Brimington and Tapton Miscellany 15, which can be purchased from us and is fully referenced.

2 thoughts on “The Plague in Brimington – 1”