This is part three of a series of blogs looking at the plague in Brimington, which was present in the community from late 1603 to early 1604

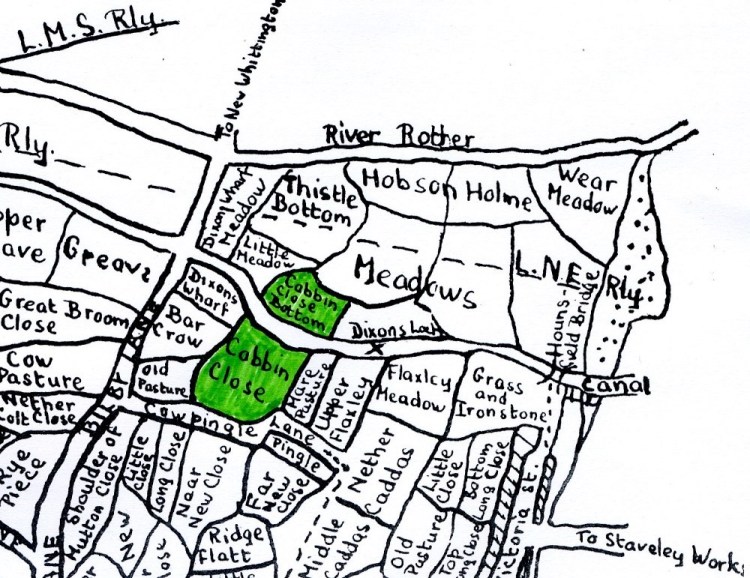

In parts one and two we have looked at the almost certainly incorrect tradition that plague victims were buried in a field – Cabbin Close at the bottom of Bilby Lane. This field was intersected by the canal when it was built in the 1770s. We also looked at why this story of plague burial might have started.

In this blog we look at what has happened to these two fields. We draw the further conclusion that no human remains have been found in this area – further adding to the evidence that there have not been any plaque burials in this area of Brimington.

What has happened to the fields?

Cabbin Close Bottom has now disappeared, Cabbin Close remains, but both appear to have been subjected to opencasting operations either nearby or directly. The site of Cabbin Close can still be traced, that of Cabbin Close Bottom – on the northern side of the canal – is now buried.

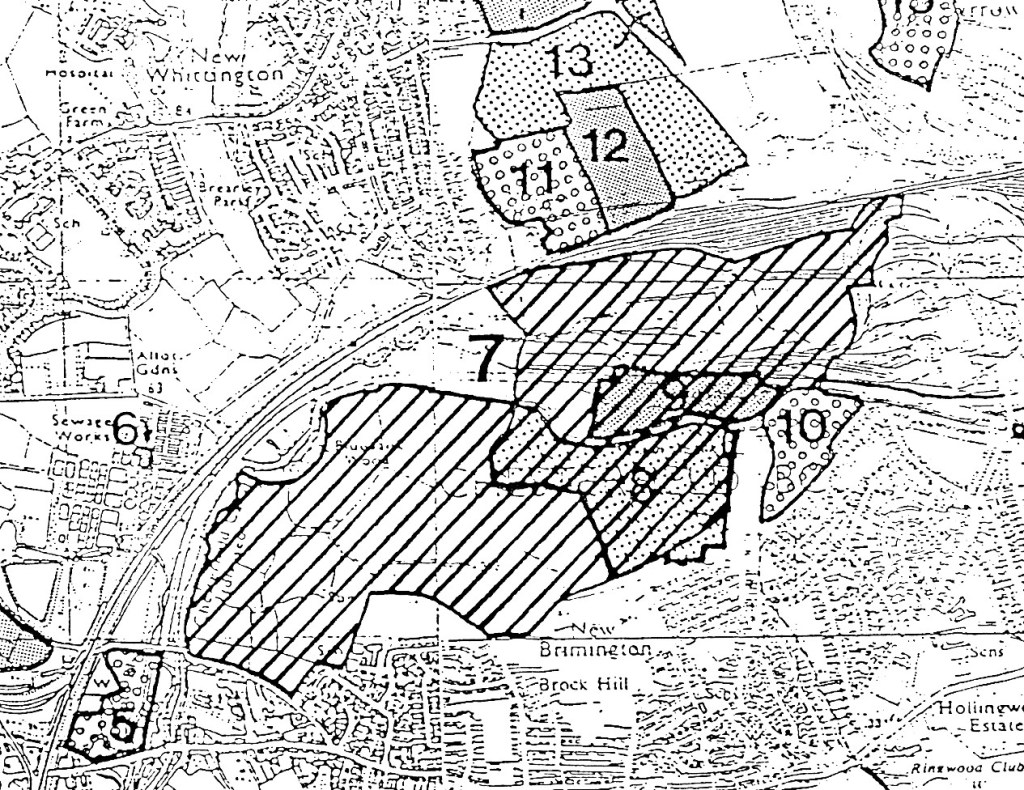

During opencasting operations at the Dixon Site, British Coal stated to a February 1987 liaison committee that the exact position of the ‘plague graves’ was not known and that the area ‘indicated on the only drawing available would not be excavated’. They further commented that no evidence had been found of the graves. British Coal also thought that the area (presumably both fields) had previously been opencasted.

During operation of the Dixon site liaison committee there were no reports of the discovery of any plague graves during the site’s operation. Although Cabbin Close was not part of the excavated opencasting operations at least part of it was used as settling lagoon area.

Let’s now look at the history of the the now separated two fields.

1 – Cabbin Close Bottom (north of the canal)

As noted, Cabbin Close Bottom was part of the 1986 to 1993 British Coal Dixon Opencast Coal Site. But it also appears to have been part of a much smaller opencast – the Bilby Lane site – around the period and up to 1985. Though it is not certain whether the field was actually excavated at this time, in 1983 the site was buried beneath an opencasting tip – presumably from the then operational Bilby Lane site.

Looking at maps we can build up a picture of land use.

In 1876 (large scale Ordnance Survey) the field boundary was much as it had been at the time of the 1827 rating survey and the 1840s Tithe apportionment and enclosure awards. But by 1898 a small field to the east had also been subsumed into the greater Cabbin Close.

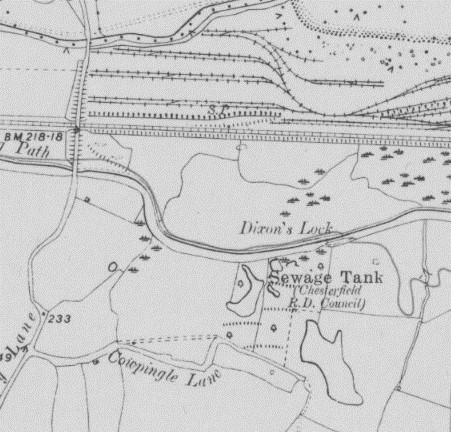

Sometime between 1918 and 1938 the field had been thrown together with yet another field on its eastern edge (the unnamed field directly above Dixons Lock on Brelsford’s map). This addition is denoted as mostly marsh-land on the 1938 large-scale Ordnance Survey map.

Further mapping evidence shows that stockyard and tipping operations from Staveley Works did not initially affect Cabbin Close Bottom, as the nearby former Great Central Railway (GCR) Chesterfield loop formed a barrier between the works and fields adjacent to the canal.

By the time of a 1955 map part of the field boundary remained recognisable, that to the east has, like of the 1938 map having disappeared. By 1961 the boundary had become more ill-defined – indicating that it was perhaps derelict land. By 1977, with closure of the former Great Central Railway Chesterfield Loop (in 1963) the field boundary area was mainly covered by a disused tip, with a nearby ‘spoil heap’ present. Both were associated with Staveley works. In 1983 an Ordnance Survey map denotes that the whole area is covered by ‘Tip (disused)’.

Now (2023) the site is buried under an embankment of fill following completion of the Dixon site and is landscaped. If the Harworth Group’s 2022 regeneration plans for their part of the Staveley Works site regeneration go-ahead Cabin Close Bottom will end up underneath housing and associated landscaping.

2 – Cabbin Close (south of the canal)

The boundary of Cabbin Close (the field south of the canal) is still partially traceable and remains in agricultural use. It immediately abuts Cowpingle Lane – the short track which branches eastwards from Bilby Lane. However, today its eastern boundary has disappeared – with two adjacent fields (Mare Pasture and Upper Flaxly on the Brelsford map), having been subsumed into it.

Mapping evidence shows that the field boundary remained unaltered until sometime between 1938 and 1947, when part of the boundary between Cabbin Close and the adjacent field to the east is shown as undefined.

By 1960 the site appears to have been tidied up – there is an absence of what had previously been a small area of marshland to the north-west corner of the field. The field to the east has been fully included within the Cabbin Close boundary. A nearby former sewage tank and watered/marshland area in the eastern field (i.e. not historically part of Cabbin Close) have also gone.

In 1926 nine acres of land ‘adjoining a prolific outcrop’ situated in Cowpingle Lane, was being offered for sale by tender by W Austin of Fairfield, Brimington. This outcrop may well be that referred to by Vernon Brelsford in his 1937 History of Brimington, when he wrote; ‘Four fields adjoining Cowpingle Lane, having an acreage of about 12 acres, have been practically made useless for years for pasture or arable land, by digging there in search of coal during the last “coal strike” in 1926‘.

Examination of an August 1945 RAF aerial photographic survey shows that the fields on Brelsford’s map denoted as Nether Caddas, Upper Flaxley and Mare Pasture have what looks like extensive ground-works on them. There is evidence that Cabbin Close itself has or is being worked at this time, with ground disturbance and tipping activities noticeable.

Additionally, the 1941 Ministry of Agriculture Survey schedule map (in The National Archives) shows Cabbin Close as ‘Tip’ (along with ‘Bar Crow’ field, shown on Brelsford’s map).

The conclusion here is that Cabbin Close has been worked twice for coal previous to the Dixon Opencast Coal Site of the 1980s/early 1990s, possibly piece-meal from the 1920s, then more widely in the c.1957 Cowpingle opencast. Prior to this it had been arable (cultivated) land. Again, as discussed earlier, during this period (and the much earlier canal construction) there have been no reported discoveries of skeletons and the like.

Taking things forward to the Dixon site operations and again as discussed earlier, south of the Chesterfield Canal was mainly designated as an over-burden tipping area. The vast majority of the extraction took place to the north and west of the Dixon site – not in the area of Cabbin Close, although at least part of the former field was used a settling lagoon, and therefore at least partially disturbed.

Cabbin Close Farm

Finally, for the sake of some completeness, it is worth mentioning the short-lived Cabbin Close Farm. This does not appear on a 1977 large scale Ordnance Survey map, but was present up until opencasting operations commenced in the summer of 1986. It is probably the small-holding of a Mr Longson ‘of Cowpingle Lane’ who in October 1983 was described as earning ‘his entire living from his farm.’

Immediately before the Dixon site commenced, the farm (actually a small-holding) was noted on a British Coal map of the Dixon site as complete with ‘caravan dwelling’.

The field was restored to grass-land as part of the Dixon site restoration but its eastern boundary has still subsumed what Brelsford’s map shows as Mare Pasture.

Longson subsequently moved to Ringwood Farm – his interests at Cowpingle Farm presumably having been acquired by British Coal as part of the Dixon opencast operations.

What does all this tell us?

During all this activity across the two fields, the existence of any human remains has never been reported – and some of the activity would have been quite intrusive. Rather like the documentary evidence this all points to there never having been any plaque burials in Cabbin Close.

Our next blog on this subject will summarise the evidence already presented across these three blogs. Part four in the series will look at another aspect of the plague in the Brimington – how Newbridge Lane came to be constructed.

Part 1 in this series of blogs about the plague in Brimington can be found here, with part 2 here.

This account is edited from ‘The plaque in Brimington (1603-1604) part 1 – were there plague burials at Cowpingle Lane?’ That account appears in our Brimington and Tapton Miscellany 15, which can be purchased from us and is fully referenced.

One thought on “The plague in Brimington – 3”